Website Search

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

In Bolivia, as in the rest of Latin America, the pleasure of the text, in Roland Barthes’ terms, has been a luxury for the few, withheld from the immense majority of men and women, boys and girls, adults and the elderly as a fundamental right, the right to culture. One main reason for this, is the elevated cost of the book. And yet, despite that in recent years pirated books have penetrated social layers where reading has been denied. The act of reading itself has deteriorated to the point of putting the entire circuit, author, distributor, and public consumer, at risk. The lack of value given to the book and literature as cultural products is even more worrisome, and perhaps because folklore is the only framework allowed to culture in Bolivia.

Without a doubt, the absence of a circuit for book production (moving beyond the cultural) has occurred because of each government’s respective lack of political initiative. For this reason, this cultural experience (the circuit of book production) has become a responsibility assumed by incompetent public officials. For example, a pseudo‐indigenous who became president when supported by incapable masses, due to human distraction. This event signals the importance of using the world of books to find ways that might help us escape the historical confusion in which we find ourselves.

During the 80’s and 90’s, democracy in Bolivia suffered the attacks of liberal governments unable to mobilize, much less make viable popular aspirations for change. Of course, despite the legitimate hopes of the majority, rotting structures afflicted the nation state to its core. Displaced sectors demanded a new state with a new face capable of offering opportunities for its citizens to utilize all of their capabilities. At the beginning of the current decade, Bolivians witnessed the collapse of traditional institutions: the enormous social contribution in search of delayed vindications; the water war in Cochabamba that not only reduced water taxes but also expelled the company Aguas del Tunari S.A. during the Black October, when the local alteño boards committee forced Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada to abandon the country. Even more significant are the marches for tierra y territorio by the indigenous communities from Eastern Bolivia in pursuit of a new state constitution. The demands for autonomy made by a few regions in the country are equally significant because of the abhorrent paceño centralism that has delayed the development of other regions. This panorama gives way to the emergence of ethno‐cultural populisms along with the surfacing of counterculture movements seated mostly in the populated, urban El Alto municipality gripped by extreme poverty, delinquency, youth gangs, and the constant search for identity. The political hegemony of the country has remained in the hands of the leftist Aymara world that, over five years under an indigenous‐marxist government, is leading Bolivian society down an extremely dangerous path of confrontation and the continued destruction of a national unity. Within the vagaries of the State’s extractionist economy, the democratic and political crisis strikes not only the most underprivileged sectors, but society as a whole. One of the areas affected by this panorama is Bolivia’s publishing industry, which lives on the threshold of collapse.

Literature in Bolivia has not been alienated from historic experience. Dr. Hernán Siles Suazo of the UDP (Unidad Democrática Popular) and the rise of the Government for Popular Unity’s consolidated a return to democracy. The euphoria of populism quickly brought bankruptcy and the population’s distrust. An enormous crisis swept the eighties. Amidst this social and political reality, literature adopted a critical perspective that was simultaneously one of compromise because it was not partisan or ideological but quotidian. One title about this era of disenchantment in Bolivia is Jonás y la ballena rosada by José Wolfgang Montes Vanucci, which deals with the climate of intemperance in the country during the Democratic Unity Government. During the initial stage of the return to democracy, Bolivian literature was stunted by an ongoing provincialism imposed by indigenist literature that allowed neither development nor experimentation with form through language. Nevertheless what is known as the novela de la guerrilla marked an important change. For example, Los fundadores del Alba (1969) by Renato Prada Oropeza, winner of an award from the Casa de las Américas, experiments with new stylistic forms, so do Matías el apóstol suplente (1971) by Julio de la Vega, La oscuridad radiante (1973) by Oscar Uzín Fernández and Tiempo desesperado (1978) by José Fellman Velarde. La Guerrilla en Bolivia, Ñancahuazú (1967) and Teoponte (1970) became important themes within the novela de la guerrilla and they generated abundant literary production. The fashionable theme on the political side was the collapse of foquismo in Latin America and the culmination of revolutionary Christian thought, but the most notable subject at this time in Bolivian history was the strategic military downfall of Che and the left in Bolivia, which resulted in a change in intellectual consciousness that assumed a non‐conformist stance and brought about a true agreement with the historic moment.

The novel of democracy focuses on urban issues as never before in Bolivian literature. After the eighties the population began to concentrate in the country’s most important urban centers, promoting a hybrid, mixed and contaminated culture. With different crossings that are not only thematic but also formal, novels like Morder el silencio (1980) by Arturo Von Vacano, American Visa (1977) by Juan de Recacochea, Margarita Hesse (1997) by Manfredo Kempff Suárez, El Delirio de Turing (2003) by Edmundo Paz Soldán, La Guía del picaflor (2004) by Juan Claudio Lechín, El Señor don Rómulo (2006) by Claudio Ferrufino‐Coqueugniot, and El tesoro de las guerras (2007) by Homero Carvalho Oliva, get close to the complex reality of this country’s background of democracy and politics woven into society at the end of the twentieth century and at the beginning of the twenty first.

It is within this economic, political, and literary context that Mandrágora Cartonera situated its first actions and editorial proposal. From our project’s beginning, accessibility to the book has constituted the central axis that we’ve attempted to bring forward as a democratic proposal open to free expression. We know for certain that a project framed by these parameters could be a competitive alternative to the larger commerce of the book although it is difficult to achieve. After the nineties and with the implementation of the structural adjustments imposed by the World Bank across Latin America, problems of social exclusion left thousands of men and women on the streets, condemned to the flagellum of the unemployed and to the inhuman voracity of the huge Latin American cities. Although cartonera books pass through a moment of euphoria, exoticism and fascination due to the fact that they begin in the garbage, constructing a text from the waste generated by people and making something with the hands of those considered to be human refuse, like the cartoneros, has a lot to do with Samaritanism. As a Brazilian theologian once said, “garbage didn’t come from the mind of God but from the mind of man.”1 However, one must remember that the idea to use cardboard as an instrument of cultural transmission is not new. In 1989, the museum Rayo in Colombia, under the sign Ediciones Embalaje, published books in editions of two hundred copies signed by each poet and illustrated by the artist Omar Rayo. These were books whose designs like El rey ilusión by Homero Carvalho constituted a work of art with a unique aesthetic in South America.

In 2005 when Javier Barilaro came to Cochabamba, we began to make our way without the slightest intention to appear in the mass media and much less to jump into stardom within the literary community. Since the beginning, our motivation has been the silent work of distributing all kinds of literature and the promotion of reading. We began working with homeless kids but we quickly realized that making artistic and literary texts was just a tear in the sea of suffering in the lives of these excluded and marginalized beings. The combination of poverty and literature proved crucial. We thought that the literary experience might embrace a long held hope for improved living conditions. We sustained this thought with the naïveté of a child waiting for a piece of candy. “In contrast to the accumulation of riches in the hands of a minority at the cost of poverty for many, reading from the garbage, from the ghettos of the market, from (and with) what lacks the most elemental material goods” is an act that instills hope. It is all about turning cardboard, a residual material, into a vehicle of cultural diffusion along with the seal and treads of narrative, poetry, and essay (philosophical, political, sociological, human rights). As a socio‐cultural literary movement, whose goal is not to make profit, the cartonera publishing houses follow the rich tradition of Latin American literature and become hope for “the poor who lack not only material goods but also, on the plane of human dignity, social and political participation.”

The cartonera movement anchors its purpose and proposal in the affirmation of the human being as a living and corporally bound subject. Practice and literature embrace one another in order to search for the recognition of this excluded and marginalized other. Cultural liberation should begin with mutual recognition between people as subjects of common rights and obligations. As long as the gulf of unjust inequality is maintained, there will be no recognition at all. This is the visible face of the social disparity between some (the privileged) and others (the deprived). For the Ecuadorian David Sánchez Rubio, “poverty expresses the refusal to recognize some people as natural and corporal beings.”2 The central considerations found in our concept of “reading from the garbage” denote a new horizon that marks the ecological problem of wastefulness. The harmful logic of the dominant systems of accumulation and social organization causes the impoverishment of humanity and the depletion of nature. Reading from the garbage is a response to this perverse logic that generates a regime of exploitation and cruel exclusion. Literature and practice, work and distribution, hope and cumbia, all guarantee a project of life, a breath of elemental dignity and survival.

As Mariano Azuela would say, literature is the bastion and safeguard of hope that cannot be denied to the underdogs. It is their way out and it is the social and political dimension of the liberation. Ignacio Ellacuría called it “historical reality or practical historical liberation.”3 Here is our fight for the most necessary. Sánchez Rubio affirms, “importance and interest will take root as long as social life and historical context are spaces for social disagreement and where human dignity can be fought for.”4 The cartonero(and many like him) is the haggard face punished by a system that limits human life and eliminates hope. “The present day global capitalist system limits huge collectives’ capacity for action so that they are unable to participate in public events and are prevented from having equality within the conditions of distribution of material goods that form social production.”5 These are normally in the hands of polyarchy and minority groups. This stance has been crumbling gradually. The emergence of Neoindigenisms and Populisms with Marxist roots has shown us that we cannot follow this path converted into a nest of spiders and birds of prey that deal in human suffering. Hence, making books with cardboard covers does not end the despoliation of humanity that enormous conglomerations of people, far and wide across this subcontinent, suffer. To Mandrágora Cartonera, it is much more productive to sustain the philosophy of a book‐object with concrete esthetic ends: the pleasure of an object at a low price and with small circulation that does not renounce its exotic condition.

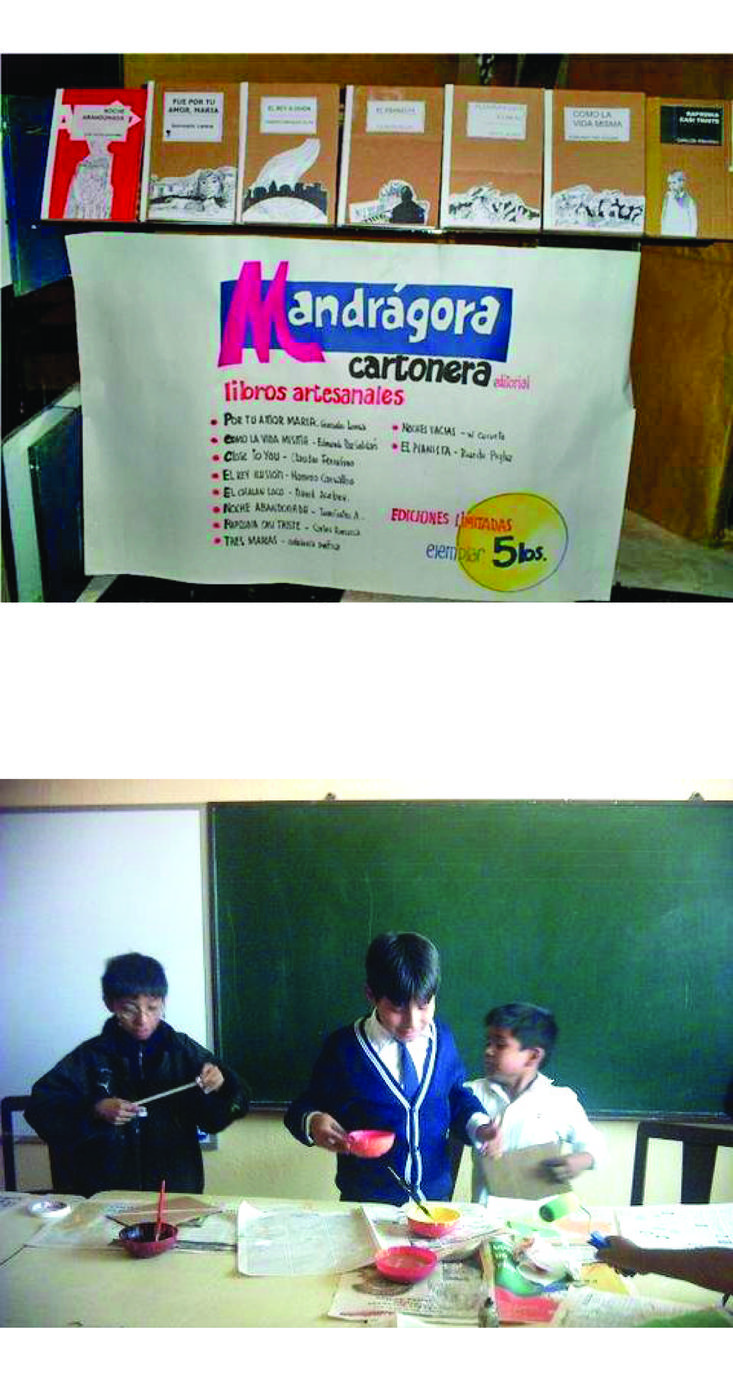

Mandrágora Cartonera is a literary publishing house that offers readers a book with a cardboard cover that was used, collected, purchased or sometimes donated by companies or private institutions, and then later assembled by hand by disabled children at the center for audiology, Fe y Alegría (a Latin American movement for integral popular education and social development). The objective of our press is to maintain the quality and coherence of its catalogue and to grow with the authors who form it. This standard was the only way to disperse the doubts that we held regarding our belief that even with limited editions our books could still lift someone from the underworld of garbage. The excellent reception that Mandrágora Cartonera has received from both readers and critics, confirms that we are on the right track in regard to our search for authors and works. In order to achieve this, Mandrágora formed a small group of professionals whose fundamental characteristics uphold the concept of literature as art, a passion for reading, enthusiasm for publishing, and the desire –strained to the point of being quixotic– to create a non‐profit business.

So far the press has published forty titles, with many more to come, in series such as Lectura desde la basura (Reading From the Garbage; a collection of contemporary Latin American and Bolivian narratives in Spanish), and Ensayo desde la basura (Essays From the Garbage; a collection of literature, philosophy, politics, education and human rights). Mandrágora has always searched for respectful and direct contact between the editor and author. This can only be done with an intense understanding of the work and respectful editing. After asking for copyright the editor makes a commitment to distribute the author’s work by giving it the widest reach possible. We are very careful with the promotional aspect of our work as much for editorial interests as for our responsibility to the author. So far we have achieved this. Unlike the light literature which inundates our society and is most attractive to our youth, we believe that we should defend literature based strictly on aesthetic criteria. That said, with our promotion of reading we hope to attract young readers and encourage them to read works that are engaging, like the classics of universal literature.

When we publish a text we do not only launch it into good conditions in the market but also bear the responsability of releasing it to its fortunes in the hands of an anonymous public. It is necessary for the work to leave its creator and to follow its own destiny among readers because a text and an author exist as autonomous and free phenomena. This process has been part of great works like Don Quixote or the Illiade. We could also think of an opening of an art exhibit where an artist renounces authority over his creature, declares its birth, and puts it up for sale on the gallery walls. The same thing happens to the book in the hands of an editor.

The decision to publish a certain text and/or author is one that fundamentally deals with a birth. This creative violence has two parts: rupture (painful separation) and, at the same time, the beginning of a new autonomous and free existence. One could liken the role of the editor to that of the obstetrician. The obstetrician is neither the force of life, nor the person who fertilizes or gives a part of the body; but without him the conceived work carried to the limit of creation would never come to be. The editor is the obstetrician of the book, or, at least in a peculiar way, “the supposed father” of the text. This is just one of many essential parts of publisher’s job. And to complete this metaphor our doctor‐surgeon must also be prenatal advisor, judge over the life and death of the newly born, hygienist, pedagogist, priest, dealer of slaves who puts a breath of life into the new being, the book.

At Mandrágora Cartonera we know that the editor is a recent character in the history of literary institutions and we therefore strive to give it the best future. Without a doubt, the methods to multiply the written word and to disseminate a text have existed since antiquity, but due to the changing technology at our disposal today there are new ways. Our press publishes in record time, which is something unthinkable for international publishing houses with enormous print runs of forty titles or more. In the past, the author was often responsible for editing the text in order to have his intellectual work known; think of Pablo de Rokha in Chile or Jorge Suárez in Bolivia. Furthermore, public readings, a favorite mode of publishing in antiquity even after the invention of the printing press, continue to be one of the best ways to share a text.

There was nothing new in terms of editing until the appearance of the book, starting with the manuscript. In the Athens of Aristotle, after the fifth century and in Rome during the classical period there were workshops for scribes, scriptoria, where mauscripts were copied. Today, publishing houses employ people to bind the books. Later the copies were sold in real bookstores. Thus, there was already an industry and commerce of the book. The biggest editions that are worth mentioning (although rare) never had more than a few hundred copies, but the idea of publishing was born. We should be aware that the Romans turned to the root of the verb edere, which means “to give birth, to bear” to denominate the act of a book’s construction, but it would be much later when Pliny used the expression for the modern editor and spoke of libelli editione digni, while Wynkyn de Worde, after Caxton, set up a small shop on Fleet Street that was, in the modern sense of the term, the first bookstore in England. The complexity of the industry soon provoked the successful and powerful printers to leave the commercial function, sale, design, and distribution in the hand of the specialists. This was how the bookseller or book vendor first appeared. At the beginning of the nineteenth century a new character surfaced in the chain of book production: the editor. This person relegates the technical function to the printer and the commercial function to the bookseller. The editor takes on the initiative of publishing and coordinates the fabrication with the necessities of the sale. The editor also deals with the author and diverse subcontracting parties, managing the separate acts of publication within a general production. Today’s editors did not neglect this commercial vision of the act of editing a text.

The editor’s job, without reducing it to its strictly material operations, can be summarized in three verbs: to choose, to fabricate, and to distribute. These three operations are mutually connected and condependent. Together they form a cycle that constitutes the editing process. These three operations correspond respectively to three essential positions on an editorial board: literary committee, production office, and commercial department. This is the structure within our publishing house. The figure of the editor is fundamental in these three operations. The editor coordinates action, gives meaning, and assumes responsibility. Even when the editor is anonymous and house politics are fixed by administrative agreement, the individual director, advisor, or administrator must conserve the moral and commercial responsibility for the entire project in order to give necessary individuality and personality to the publication in question. The rigorous esthetic behind the editor’s selection envisions a potential public and selects from the mass of writings those that will appeal to public. The editor must make a factual judgment about what the public desires and must also make a value judgment regarding what the public will like. Is the chosen book marketable? Is it good? Does it have the characteristics of a literary text? The answers to these questions reflect the needs of the public who will in turn benefit by the selection.

Finally, it is important to keep the reader in mind throughout this circuit between the public, the editor, the author, and the book object from the search for the author and the text until the final publication. Even when dealing with a cheap book, like a cartonera text, everything enters into play: paper, size, characteristics, typography—selection of the type face, justification, density of the pages, etc.—, the illustration, binding, the finished product, and above all the number of copies. From here, the editor must calculate the impact he or she hopes to make. The forty titles behind us are the indelible footprints of our efforts to think about the public and potential future readers. With the reduced cost of our books, we want literature to be for all.

Members of Mandrágora Cartonera: Carlos Rimassa,

Elena Ferrufino, Nicolás Gómez, Iván Castro.