Website Search

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

At an early hour on the morning of , I began to pack up my baggage, and make the final preparations for my departure to the north. The horses being caught, my servant proceeded to load them, which was accomplished in the following manner. Large square pieces of a thin fibrous turf were laid on the horses backs, above which was placed a kind of p. 24 wooden saddle, called, in Icelandic, klifberi, that served the double purpose of keeping the turf together, and supporting the baggage, which was suspended on two wooden pegs, fixed one on each side of the saddle. The whole was fastened by means of two leathern thongs that went round the belly of the horse. Having partaken of an excellent breakfast at the Sysselmand’s, we sent the baggage on before us; and, bidding adieu to our friends in Reykiavik, we set off about twelve o’clock, accompanied by Mr. Edmund Hodgson, a gentleman from England, and Mr. Vidalin, one of the Bishop’s sons, who intended to proceed with us as far as the Geysers. Mr. Knudsen also conducted us to the Laxâ, or Salmon River,1 which falls into the bay about four miles to the east of Reykiavik, and abounds in the excellent species of fish from which it derives its name. A little farther on, we fell in with our baggage, and could not help smiling at the striking resemblance our whole company bore to a band of tinkers. However, I was soon reconciled to the mode of travelling, on discovering that it was quite oriental, and almost fancied myself in the midst of an Arabian caravan. In fact, there exist so many coincidences between the natural appearances of this island, together with the manners p. 25 and customs of its inhabitants, and what is to be met with in the East, that I must claim some indulgence from the reader, if I should occasionally allude to them, especially as they tend to throw light on many passages of Scripture. Our horses formed a pretty large cavalcade, amounting to not less than eighteen in number. The first was led by one of the servants; and the rest were tied to each other in a line, by means of a cord of hair fastened to the tail of the one that went before, and tied round the under jaw of the one that followed. Owing to this mode of leading them, it is of importance to have horses that are accustomed to it, otherwise they are sure to drag behind, and when any of those that go before happen to leap over a torrent, or begin to trot, the unbroken ones are taken by surprise, heave up their heads, and generally break the rein. In this case, if your servant be careless, and no person brings up the rear, you may proceed for a mile or two without discovering that the half of your cavalcade is amissing. The Arabs have an effectual method of guarding against this inconvenience, by fixing a small bell round the neck of the last camel in the row. Sometimes the horses are suffered to go loose, in which case they are driven before the travellers; and, should any of them stray from the path, a certain call from the guide is sufficient to bring them back.

The first part of the road was by no means p. 26 calculated to inspire us with very favourable ideas of the country; for little else appeared around us but vast fields of stones and comminuted lava. On the left hand, at no great distance, we had the continuation of the Esian mountains, the western extremities of which face Reykiavik; and a little before us, on the same side, lay the Skâlafiall, whose three pyramidic tops were towering high above the clouds. About six in the evening we arrived at Mossfell, which stands on an eminence, and commands an extensive, though rather barren prospect. The church is built of wood, has a coat of turf around the sides, and the roof consists of the same material. It has only two small windows at the east end, and a sky‐light to the south; and the whole structure does not exceed thirteen feet in length, by nine in breath. We did not find the clergyman at home; but his wife treated us with plenty of fresh cream, and we were quite delighted with the frankness and agility with which she performed the rites of hospitality.

Leaving Mossfell, we entered a moor, which, from west to east, the direction in which we travelled, was certainly not less than eighteen miles. The ride was dreary in the extreme. For more than five hours we did not see a single house, or indeed any living creature, excepting a few golden plovers, which, from their melancholy warble, only added to the gloominess of p. 27 the scenery. At midnight we reached the western margin of the Thingvalla Lake, and stopped at a small cottage called Skâlabrecka. All, of of course, was shut; but we followed Captain Von Scheel, who scaled the walls, and each of us endeavoured to find some window or hole in the roof, through which we might rouse some of the inhabitants. It was not, however, till the Captain had forced open one of the doors, and called as loud as he was able, that we effected our purpose. The salutation he made use of was, Her se Gud, “May God be in this place;” which, after he had repeated it near a dozen of times, was answered with Drottinn blessa thik, “The Lord bless thee.” My imagination led me instantly to the field of Boaz, Ruth ii. 4.; and I felt all the force of our Saviour’s injunction: “When ye enter the house, salute it; and if the house be worthy, let your peace come upon it.” Math. x. 12, 13. The common salutations of the Icelanders are most palpably oriental. On meeting a person, you hail him with Sæl vertu, which exactly corresponds to the Hebrew Shalom lach; or the Arabic Salam aleik: neither of which signify “peace,” in the occidental sense of the word, but “I wish thee happiness, or prosperity.” It would appear, from the Edda, that the ancient Scandinavians used Heill instead of Sæll, whence, through the medium of the Anglo‐Saxon, our English “hail,” which occurs as a salutation in many parts of the p. 28 Bible,2 The person you salute generally replies, Drottinn blessa ydr, or Blessa ydr Drottinn, “The Lord bless you.” When you meet the head of a family, you wish prosperity to him, and all that are in his house, (see 1 Sam. xxv. 6.); and, on leaving them, you say, Se i Guds Fridi, “May you remain in the peace of God;” which is returned with, Guds Fridi veri med ydr, “The peace of God be with you.” Both at meeting and parting, an affectionate kiss on the mouth, without distinction of rank, age, or sex, is the only mode of salutation known in Iceland, except sometimes in the immediate vicinity of the factories, where the common Icelander salutes a foreigner whom he regards as his superior, by placing his right hand on his mouth or left breast, and then making a deep bow. When you visit a family in Iceland, you must salute them according to their age and rank, beginning with the highest, and descending, according to your best judgment, to the lowest, not even excepting the servants: but, on taking leave, this order is completely reversed; p. 29 the salutation is first tendered to the servants, then to the children, and, last of all, to the mistress and master of the family.

The remoteness of the sleeping apartment, which lay at the inner end of a long narrow passage, could not but render it difficult for the people to hear us; however, they soon began to make their appearance; and, instead of looking sulky, or grumbling at us for having disturbed them in their soundest repose, they manifested the utmost willingness to serve us; and assisted us in unloading the horses, and loosing our tents, which we pitched close to the lake. The Icelandic tents pretty much resemble those of the Bedoween Arabs, and are erected in the following manner: two poles, of from five to six feet in length, are stuck fast in the ground, at the distance of seven or eight feet, and joined together at the top by a third pole, over which the curtain, consisting of white wadmel, or coarse woollen cloth, is spread, and braced tight by means of cords fastened to the eaves, and tied at the other end to hooked wooden pins, which are driven into the ground at different distances round the tent. The flaps are provided with small holes around the border, and are fastened close to the ground in the same manner, except at the one end, where a small piece is left loose to serve the purpose of a door. In these tents the natives live several weeks on the mountains every summer, while they are p. 30 collecting the lichen Islandicus, and are extremely fond of this kind of Nomadic life.

Our friend, Captain von Scheel, lay on an excellent bed, supported by two long wooden poles, fixed at each end to the top of his travelling chests, about a foot and a half above the ground; and this commodious method I also adopted on my arrival in the north: but at present I was obliged to spread my couch on the ground, from which I was separated only by the flat pieces of turf that had served as packsaddles; and my riding‐saddle, placed on its back, formed an admirable pillow. To prevent the horses from running away, their fore‐feet were tied together with a rope of hair, in the one end of which was an eye, and the other was wound round the ancle‐bone of a sheep, and thus fixed in the noose. As the morning was rather cold, we got a supply of warm milk, which proved very refreshing; and a little before two o’clock, I sat down on one of the wooden boxes, at the door of my tent, and read the 103d Psalm, in my small pocket‐Bible—so clear are the summer nights in this northern latitude. Lifting up my heart to my Heavenly Father, I humbly presented my tribute of praise for the mercies of the past day, and retired to rest in the possession of a high degree of comfort and peace.

Having reposed about six hours, I drew aside the curtain of my tent door, when the Thingvalla‐vatn presented itself full before me, near the p. 31 middle of which the two black volcanic islands of Sandey and Nesey rose into view. On the opposite side, a rugged range of mountains, above which the sun had just risen, stretched along to the right; and the prospect was bounded on the south by a number of mountains, diversified in size and form, but all of which appeared to owe their birth to the convulsive throes of the earth, occasioned at some remote period by the violence of subterraneous fire. The inhabitants of the cottage seemed very poor; and though they were in possession of a few books, had no part of the Scriptures. I therefore presented the peasant with a Bible, which he received with every demonstration of gratitude and joy.

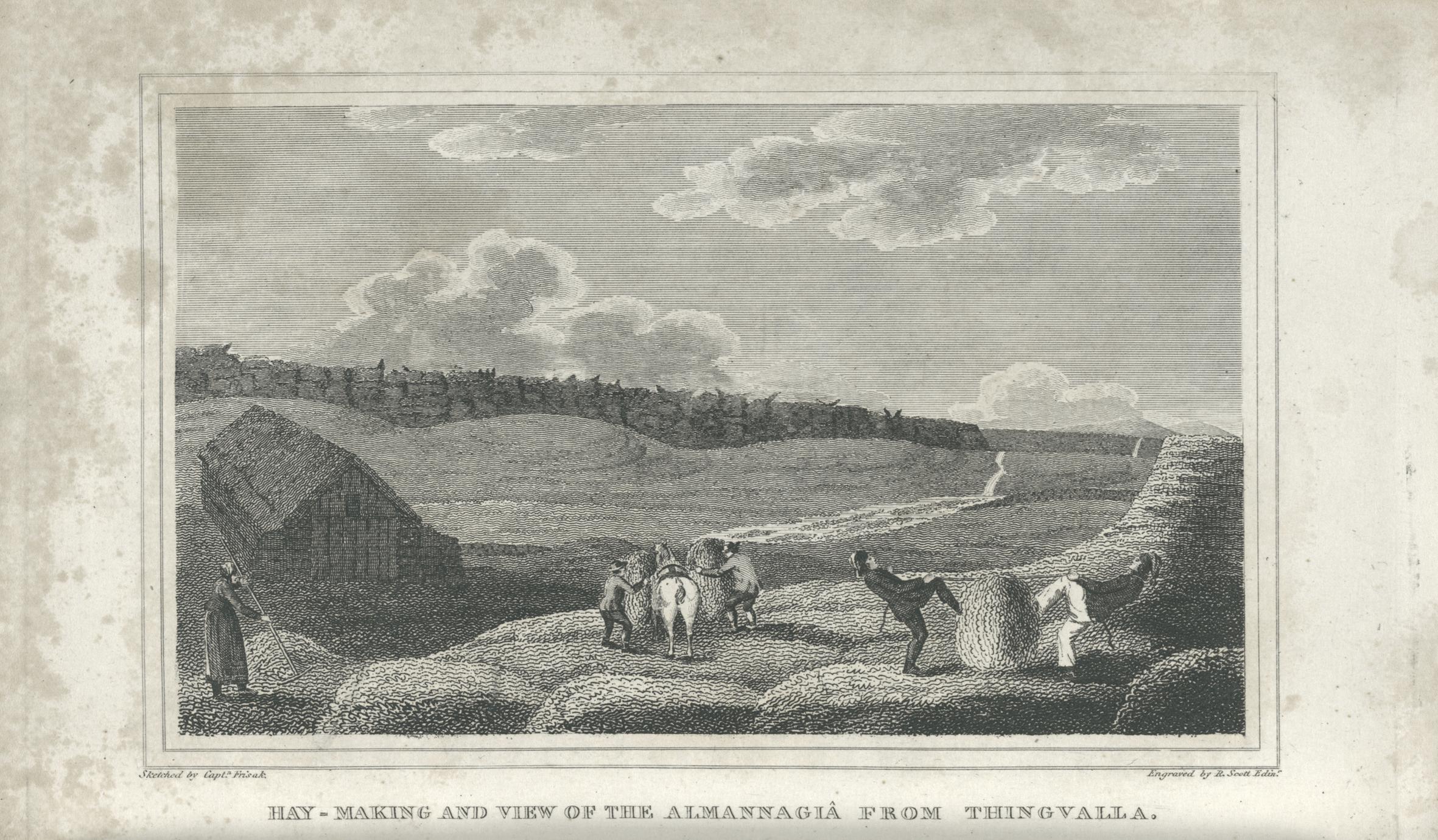

After bathing in the lake, the bottom of which consisted of the finest particles of lava, and partaking of a dish of warm coffee, which I contrived to boil on the ground, we set off for Thingvalla, across a plain entirely covered with lava; but, as it was smoother and less broken, we rode over it without much difficulty. The track we followed led us all at once to the brink of the frightful chasm, called Almannagiá3, where the solid masses of burnt rock have been disrupted, p. 32 so as to form a fissure, or gap, not less than an hundred and eighty feet deep; in many places nearly of the same width; and about three miles in length. At first sight, the stupendous precipices inspired us with a certain degree of terror, which, however, soon left us, and we spent nearly half an hour in surveying the deep chasms, running nearly parallel with the main one, almost below our feet. On the west side of the rent, at no great distance from its southern termination, it is met by another opening, partially filled with large masses of broken rock, down which the traveller must resolve to proceed. Binding up the bridles of our horses, we made them descend before us, while we contemplated with surprise the undaunted nimbleiless with which they leaped from one step of this natural staircase to another. In our own descent, it was not without impressions of fear that we viewed the immensely huge pieces of rock that projected from the sides of the chasm, almost overhead, and which appeared to be but slenderly attached to the precipice. When we arrived at the bottom, we found ourselves situated in the midst of a fine green; and, after stopping once more to admire the wild and rugged grandeur of the scenery, we again mounted our steeds, and, reaching a pass in the eastern cliffs, which, owing to the sinking of the ground, are considerably lower, we made our egress with the utmost ease.

We now entered the Thingvalla, or Court Valley; and, crossing the river Öxerâ, by which

p.

What renders Thingvalla the most remarkable, perhaps, of any spot to which importance is attached in the annals of Iceland, is its having been the seat of the Althing, or general assembly of the nation, for the period of nearly nine hundred years. In , when the Ulfliotian Code was received by the inhabitants, the supreme court of justice, which had been held for several years at a place called Hof, in the Kiosar district, was removed to this plain; and the public concerns of the people continued to be discussed, and public justice administered here, till the year , when the dreadful convulsions which the vicinity had suffered from earthquakes, p. 34 were made a pretext for the removal of the court to Reykiavik, where it is now held. Nor was it merely the seat of civil judicature. The consistory or ecclesiastical court, under the presidency of the Bishop of Skalholt, was also convened annually at this place; and numbers repaired to Thingvalla, who had no interest pending at either court, merely for the sake of meeting their friends. It accordingly holds a conspicuous place in all the Sagas or ancient traditionary accounts, and is peculiarly worthy of notice, on account of its being the spot where the Christian religion was publicly acknowledged in the year : A decision which was hastened by the following circumstance.—While the heathen and those who professed Christianity were engaged in all the ardour of dispute, a messenger came running into the assembly with the intelligence, that subterraneous fire had broken out in the district of Ölfus, and that it threatened the mansion of the high priest Thoroddr. On hearing this, the heathen exclaimed: “Can it be matter of surprise that the gods should be angry at such speeches?” To which Snorri Godi, an advocate of the Christians, replied by as pointed a question: “At what were the gods angry then, at the period when the very lava on which we now stand was burning?” The force of the argument was felt: the assembly adjourned for that day; and when they again met, an act was passed for the abolition of all public acts of idolatry, p. 35 and the introduction of Christianity as the authorised religion.

Previous to the year , the court was held in the open air, surrounded by a scenery, the wildest and most horrific of any in nature, and awfully calculated to add to the terrors of justice, and maintain the inviolability of the civil code. “It is,” says Sir George Mackenzie,4 “a spot of singular wildness and desolation; on every side of which, appear the most tremendous effects of ancient convulsion and disorder; while nature now sleeps in a death‐like silence amid the horrors she has formed.” As the aged clergyman was unable to walk about with us himself, he begged we would allow his son to shew us the wonders of the place. We accordingly followed him a little to the north‐west of the church, when we entered on a long and narrow tract of solid lava, covered with the richest vegetation, but completely separated from the rocks on both sides, by two parallel fissures, which, in most places, are upwards of forty fathoms in depth, and in some places no bottom can be found at all. They are filled with the most beautiful pellucid water, till within about sixty feet of the brink on which we stood. It was impossible for us to look down into the dreadful abyss on either side, without being sensible of the most disagreeable emotions; and when, with the terrors of our situation, we combined the idea of p. 36 the awful period when the rocks rent and the mountains fell, we felt a desire to remove as quickly as possible to a safer and more agreeable scene. The place is called Lögbergit, or “the Law Mount;”5 and the ruins of the house occupied by the chief magistrate are still to be seen. A little below this, near the side of the river, we were shewn the spot, where, in ancient times, many a miserable wight was burned for witchcraft. On removing a little of the earth, we discovered the remains of burnt bones and ashes. Such females as were convicted of child murder, were drowned in a pool formed by the river Öxerâ, in the Almannagiâ, just before it reaches the cataract by which it descends into the plain. The other culprits were beheaded on Thorsleifsholm, a small island in the middle of the river.

After dining on an excellent dish of fresh salmon trout, a species of fish in which the lake abounds, and equally good curds and cream, we left Thingvalla, and pursued our journey round the north end of the lake. The whole of the tract consisted of lava, and, at almost every turn p. 37 of the narrow path, we fell in with chasms and apertures, which wore the most perilous aspect. The dreariness, however, of the scene, was in some measure enlivened by the small bushes of birch and willow, that every now and then reared their heads among the rough cakes of lava. In the ascent on the opposite side of the lake, is another large fissure, called Hrafnagiâ, or “the fissure of the ravens,” which forms an almost exact counterpart to the Almannagiâ, with which it runs parallel to the distance of more than two miles. It is supposed, that the whole of the intervening space was originally of the same altitude with the heights on both sides; but in one of the terrible convulsions, to which this part of the island has been subjected, the ground has sunk to its present level; and, disrupting at the same time from the adjoining rocks, these and other rents in the neighbourhood have been formed. We had here to pass a natural bridge, consisting of a thin crust of lava, little more than two feet in breadth; yet, as the Icelandic horses are uncommonly sure‐footed, and generally accustomed to traverse such rugged tracts, we preferred riding to walking, and, in the good providence of God, arrived in safety on the opposite side. We now entertained the hope of entering a more auspicious region; but after crossing a dismal stream of lava, the surface of which was covered with grey moss, and in many places exhibited large caves, we were suddenly arrested by sharp vitrified masses of broken lava, which p. 38 appears to have proceeded from a volcano close to us on the left, and on its reaching this spot to have cooled and contracted, and thus the numerous crevices have been formed which presented themselves everywhere around us. Proceeding, with wary step, we ultimately succeeded in getting across this rough and difficult tract; and descending by the south side of a large mountain, whose surface discovered but scanty traces of vegetation, we entered a fine valley, the grass of which, though coarse, was nearly two feet in length. The numerous peaked mountains to the left, and the yellowish volcanic cones at their base, exhibited one of the most romantic prospects we had yet beheld. We next crossed a barren moor, and, after winding round the foot of some lofty mountains, reached the farm of Laugarvalla, situated close to the lake of the same name, about half past eight in the evening.

Having pitched our tents on a beautiful green at some distance from the houses, and feasted luxuriously on some rich cream which we obtained from the farmer, we went, before retiring to sleep, to visit the hot springs on the margin of the lake. From most of them, the water is thrown up at irregular intervals, yet not to any great height; three feet being the highest we observed. They erupt, however, with great impetuosity, and a considerable quantity of steam makes its escape. In the hottest we tried, Fahrenheit’s thermometer stood at 212°. They appear to be p. 39 of a strong sulphureous quality, and the incrustations formed by their depositions are extremely delicate and beautiful.

The prospect we had on the , far transcended what we had enjoyed the preceding day in the vicinity of Thingvalla. We had the Laugarvalla Lake direct before us, and, a little to the south, another larger lake connected with it, and known by the name of Apa‐vatn. The large volumes of steam which rose from the spouting springs close to the farm; those which made their escape from the numerous caldrons at the south side of the lake; and especially the column, eclipsing all the rest, which was emitted from the Reykia‐hver, at the distance of seven miles to the north‐east, had the grandest effect; and, viewed in conjunction with the widely extended plain, intersected in various parts by beautiful serpentine rivers, the long range of mountains to the eastward, over which Mount Hekla reared her three snow‐clad summits; those in the neighbourhood of Skalholt, and the lofty Eyafialla Yökul,6 presented altogether a landscape which only wanted wood to render it the most completely picturesque of any in the world. The clearness, too, and serenity of the atmosphere, made every object appear to double advantage. Every finer feeling of the mind was called into exercise, and I do not recollect that I ever repeated p. 40 with more exquisite delight the following lines of the Christian poet:

“Parent of good! thy works of might “I trace with wonder and delight, “In them thy glories shine; “There’s nought in earth, or sea, or air, “Or heav’n itself, that’s good or fair, “But what is wholly thine.”

We had enjoyed uninterrupted good weather since leaving Reykiavik, but now there was not a cloud to be seen in the whole horizon; the sun shone with dazzling splendour, and the heat was so intense, that it was with some degree of reluctance we left the shade of our tents in order to prosecute our journey. What proved most annoying, was an immense quantity of large musquitoes, by which our horses were sadly tormented; and, though we tied handkerchiefs over our faces, it was scarcely possible to prevent them from biting us. From Laugarvalla, our way lay along the base of several sloping mountains to the north‐west of Skalholt, till we came to the Bruarâ, a broad and rapid river, which, after receiving the joint waters of the Laugarvalla and Apa lakes, has its confluence with the majestic Hvitâ, or white river, a little below Skalholt. As there was no ferry in the neighbourhood, we were under the necessity of fording it, in the idea of which, there is something very revolting to a stranger, especially when he stands on the bank, and surveys the breadth and rapidity of the p. 41 stream. Getting the baggage tied as high on the horses as possible, and having been apprised of the necessity of keeping their heads against the current, to prevent its getting too powerful for them, we descended into the river, and our horses, after a severe struggle, succeeded in bringing us safely across.

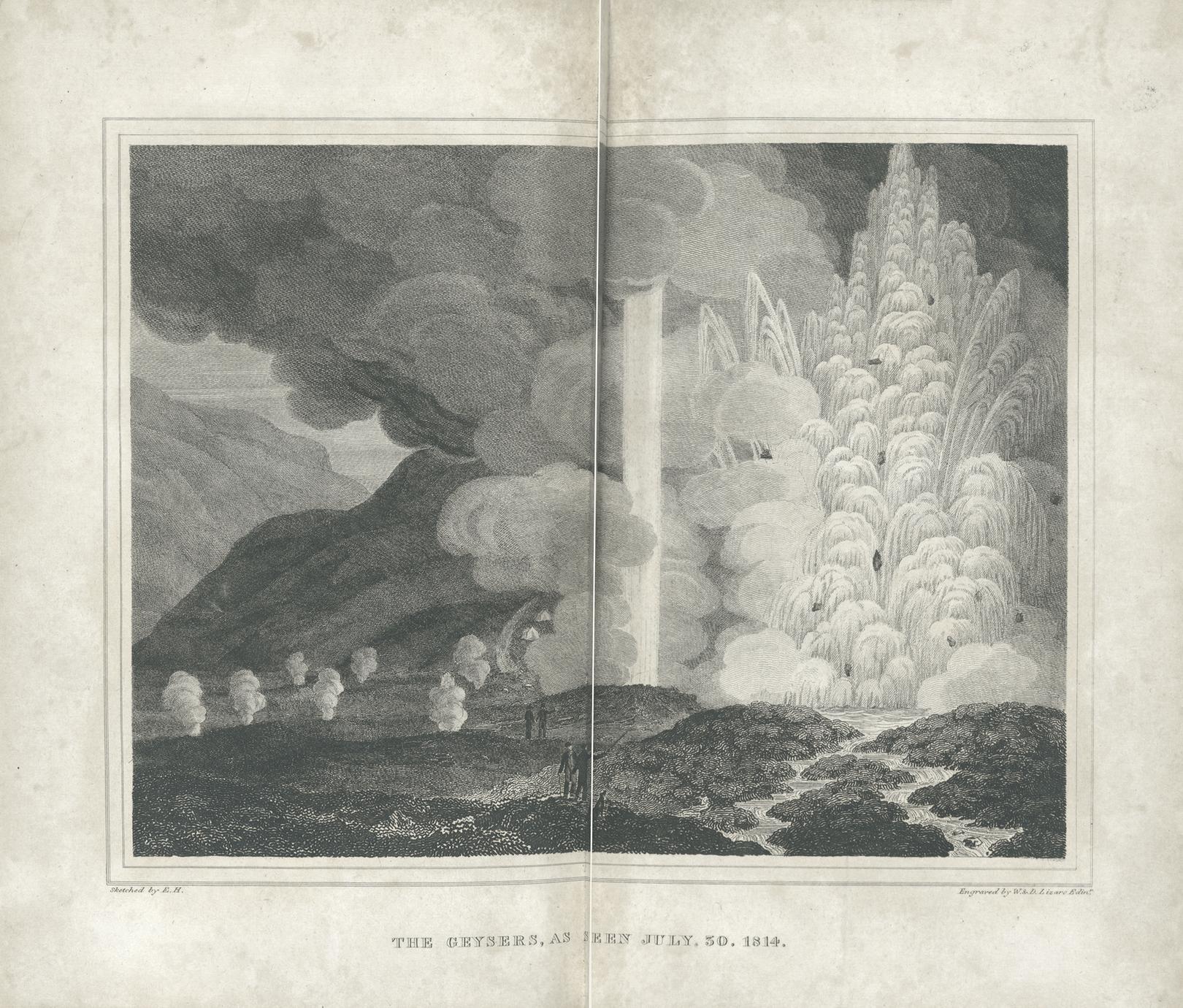

We had now a pleasant ride over the marshes to the hot springs, called the Geysers, at which we arrived about a quarter past four in the afternoon. At the distance of several miles, on turning round the foot of a high mountain on our left, we could descry, from the clouds of vapour that were rising and convolving in the atmosphere, the spot where one of the most magnificent and unparalleled scenes in nature is displayed:—where, bursting the parted ground, Great Geyser

“——— hot, through scorching cliffs, is seen to rise, With exhalations steaming to the skies!”7

Electrified, as it were, by the sight, and feeling impatient to have our curiosity fully gratified, Mr. Hodgson and I rode on before the cavalcade; and, just as we got clear of the south‐east corner of the low hill, at the side of which the springs are situated, we were saluted by an eruption which lasted several minutes, and during which the water appeared to be carried to a great p. 42 height in the air. Riding on between the springs and the hill, we fell in with a small green spot, where we left our horses, and proceeded, as if by an irresistible impulse, to the gently sloping ground, from the surface of which numerous columns of steam were making their escape.

Though surrounded by a great multiplicity of boiling springs, and steaming apertures, the magnitude and grandeur of which far exceeded any thing we had ever seen before, we felt at no loss in determining on which of them to feast our wondering eyes, and bestow the primary moments of astonished contemplation. Near the northern extremity of the tract rose a large circular mound, formed by the depositions of the fountain, justly distinguished by the appellation of the Great Geyser, 8 from the middle of p. 43 which a great degree of evaporation was visible. Ascending the rampart, we had the spacious bason at our feet more than half filled with the most beautiful hot chrystalline water, which was but just moved by a gentle ebullition, occasioned by the escape of steam from a cylindrical pipe or funnel in the centre. This pipe I ascertained by admeasurement to be seventy‐eight feet of perpendicular depth; its diameter is in general from eight to ten feet, but near the mouth it gradually widens, and opens almost imperceptibly into the bason, the inside of which exhibits a whitish surface, consisting of a siliceous incrustation, which has been rendered almost perfectly smooth by the incessant action of the boiling water. The diameter of the bason is fifty‐six feet in one direction, and forty‐six in another; and, when full, it measures about four feet in depth from the surface of the water to the commencement of the pipe. The borders of the bason, which form the highest part of the mound, are very irregular, owing to the various accretions of the deposited substances; and at two places are small channels, equally polished with the interior of the bason, through which the water makes its escape, when it has been p. 44 filled to the margin. The declivity of the mound is rapid at first, especially on the north‐west side, but instantly begins to slope more gradually, and the depositions are spread all around to different distances, the least of which is near an hundred feet. The whole of this surface, the two small channels excepted, displays a beautiful siliceous efflorescence, rising in small granular clusters, which bear the most striking resemblance to the heads of cauliflowers, and, while wet, are of so extremely delicate a contexture, that it is hardly possible to remove them in a perfect state. They are of a brownish colour, but in some places approaching to a yellow. On leaving the mound, the hot water passes through a turfy kind of soil, and, by acting on the peat, mosses, and grass, converts them entirely into stone, and furnishes the curious traveller with some of the finest specimens of petrifaction.

Having stood some time in silent admiration of the magnificent spectacle which this matchless fountain, even in a state of inactivity, presents to the view, as there were no indications of an immediate eruption, we returned to the spot where we had left our horses; and, as it formed a small eminence at the base of the hill, and commanded a view of the whole tract, we fixed on it as the site of our tents. About thirty‐eight minutes past five, we were apprized, by low reports, and a slight concussion of the ground, that an eruption was about to take place; but only a few small jets were thrown up, and p. 45 the water in the bason did not rise above the surface of the outlets. Not being willing to miss the very first symptoms of the phenomenon, we kept walking about in the vicinity of the spring, now surveying some of the other cavities, and now collecting elegant specimens of petrified wood, leaves, &c. on the rising ground between the Geyser and the base of the hill. At fifteen minutes past eight we counted five or six reports, that shook the mound on which we stood, but no remarkable jet followed: the water only boiled with great violence, and, by its heavings, caused a number of small waves to flow towards the margin of the bason, which, at the same time, received an addition to its contents. Twenty‐five minutes past nine, as I returned from the neighbouring hill, I heard reports which were both louder and more numerous than any of the preceding, and exactly resembled the distant discharge of a park of artillery. Concluding from these circumstances that the long expected wonders were about to commence, I ran to the mound, which shook violently under my feet, and I had scarcely time to look into the bason, when the fountain exploded, and instantly compelled me to retire to a respectful distance on the windward side. The water rushed up out of the pipe with amazing velocity, and was projected by irregular jets into the atmosphere, surrounded by immense volumes of steam, which, in a great measure, hid the column from the view. The p. 46 first four or five jets were inconsiderable, not exceeding fifteen or twenty feet in height; these were followed by one about fifty feet, which was succeeded by two or three considerably lower; after which came the last, exceeding all the rest in splendour, which rose at least to the height of seventy feet. The large stones which we had previously thrown into the pipe were ejaculated to a great height, especially one, which was thrown much higher than the water. On the propulsion of the jets, they lifted up the water in the bason nearest the orifice of the pipe to the height of a foot, or a foot and a half, and, on the falling of the column, it not only caused the bason to overflow at the usual channels, but forced the water over the highest part of the brim, behind which I was standing. The great body of the column (at least ten feet in diameter,) rose perpendicularly, but was divided into a number of the most superb curvated ramifications; and several smaller sproutings were severed from it, and projected in oblique directions, to the no small danger of the spectator, who is apt to get scalded, ere he is aware, by the falling jet.

On the cessation of the eruption, the water instantly sunk into the pipe, but rose again immediately, to about half a foot above the orifice, where it remained stationary. All being again in a state of tranquillity, and the clouds of steam having left the bason, I entered it, and proceeded within reach of the water, which I found to p. 47 be 183° of Fahrenheit, a temperature of more than twenty degrees less than at any period while the bason was rilling, and occasioned, I suppose, by the cooling of the water during its projection into the air.

The whole scene was indescribably astonishing; but what interested us most, was the circumstance, that the strongest jet came last, as if the Geyser had summoned all her powers in order to shew us the greatness of her energy, and make a grand finish before retiring into the subterraneous chambers in which she is concealed from mortal view. Our curiosity had been gratified, but it was far from being satisfied. We now wished to have it in our power to inspect the mechanism of this mighty engine, and obtain a view of the springs by which it is put in motion: but the wish was vain; for they lie in “a tract which no fowl knoweth, and which the vulture’s eye hath not seen;”—which man, with all his boasted powers, cannot, and dare not approach. While the jets were rushing up towards heaven, with the velocity of an arrow, my mind was forcibly borne along with them, to the contemplation of the Great and Omnipotent Jehovah, in comparison with whom, these, and all the wonders scattered over the whole immensity of existence, dwindle into absolute insignificance; whose almighty command spake the universe into being; and at whose sovereign fiat the whole fabric might be reduced, in an instant, to its original nothing. Such scenes exhibit only “the hiding of His power.” It is merely p. 48 the surface of His works that is visible. Their internal structure He hath involved in obscurity; and the sagest of the sons of man is incapable of tracing them from their origin to their consummation. After the closest and most unwearied application, the utmost we can boast of is, that we have heard a whisper of His proceedings, and investigated the extremities of His operations9.

On the I was awakened by Captain von Scheel, at twenty‐three minutes past five o’clock, to contemplate an eruption of the spring, which Sir John Stanley10 denominates the New Geyser, situated at the distance of an hundred and forty yards to the south of the principal fountain. It is scarcely possible, however, to give any idea of the brilliancy and grandeur of the scene which caught my eye on drawing aside the curtain of my tent. From an orifice, nine feet in diameter, which lay directly before me, at the distance of about an hundred yards, a column of water, accompanied with prodigious volumes of steam, was erupted with inconceivable force, and a tremendously roaring noise, to varied heights, of from fifty to eighty feet, and threatened to darken the horizon, though brightly illumined by the morning sun. During the first quarter of an hour, I found it impossible to move from my knees, on which I had raised my p. 49 self, but poured out my soul in solemn adoration of the Almighty Author of nature, to whose controul all her secret movements and terrifying operations are subject:—“who looketh on the earth, and it trembleth; who toucheth the hills, and they smoke11.” At length I repaired to the fountain, where we all met, and communicated to each other our mutual and enraptured feelings of wonder and admiration. The jets of water now subsided; but their place was occupied by the spray and steam, which, having free room to play, rushed with a deafening roar, to a height little inferior to that of the water. On throwing the largest stones we could find into the pipe, they were instantly propelled to an amazing height; and some of them that were cast up more perpendicularly than the others, remained for the space of four or five minutes within the influence of the steam, being successively ejected, and falling again in a very amusing manner. A gentle northern breeze carried part of the spray at the top of the pillar to the one side, when it fell like a drizzling rain, and was so cold that we could stand below it, and receive it on our hands or face without the least inconvenience. While I kept my station on the same side with the sun, a most brilliant circular bow, of a large size, appeared on the opposite side of the fountain; and, on changing sides, having the fountain between me and the sun, I discovered p. 50 another, if possible still more beautiful, but so small as only to encircle my head. Their hues entirely resembled those of the common rainbow. After continuing to roar about half an hour longer, the column of spray visibly diminished, and sunk gradually, till twenty‐six minutes past six, when it fell to the same state in which we had observed it the preceding day, the water boiling at the depth of about twenty feet below the orifice of the shaft.

The external structure of this fountain is very different from that of the Great Geyser. The crater, or pipe, which is about nine feet in diameter, and forty‐four in depth, is not entirely circular; neither does it descend so perpendicularly as that of the other. At the orifice it becomes still more irregular, and, instead of opening into a bason, it is defended on the one side by an incrustated wall, about a foot and a half in height, while on the other it is level with the surface of the ground.

The name given to this fountain by the natives is Strockr, which is derived from the verb strocka, “to agitate, or bring into motion,” and properly denotes a churn. Previous to the year , this name was attached to what Sir John Stanley calls the Roaring Geyser, situate at the distance of eighty yards from the Great Geyser;12 the remains of which are still to be seen, as Sir George Mackenzie rightly conjectures13, in the p. 51 irregular, but most beautiful cavity on the rise of the hill. This information I had from the peasant of Haukadal, who appeared to be a judicious and well‐informed man. He further told me, that in point of the height of its jets, the Old Strockr rivalled the Geyser; but immediately after an earthquake in the above mentioned year, it greatly diminished, and in the course of a few years became entirely tranquil. The same year, Strockr, which had not before attracted any particular attention, began to erupt, and threw up water and steam to an amazing height. This account entirely coincides with Sir John Stanley’s observations: “One of the most remarkable of these springs,” he says, “threw out a great quantity of water, and, from its continual noise, we named it the Roaring Geyser. The eruptions of this fountain were incessant. The water darted out with fury every four or five minutes, and covered a great space of ground with the matter it deposited. The jets were from thirty to forty feet in height. They were shivered into the finest particles of spray, and surrounded by great clouds of steam.”14 And, treating of Strockr, to which, as was observed above, he gave the name of the New Geyser, he adds in a note, “Before the month of June, , the year I visited Iceland, this spring had not played with any great degree of violence, at least for a considerable time. (Indeed, the formation p. 52 of the pipe will not allow us to suppose, that its eruptions had, at no former period, been violent). But, in the month of June, this quarter of Iceland had suffered some very severe shocks of an earthquake; and it is not unlikely, that many of the cavities communicating with the bottom of the pipe had been then enlarged, and new sources of water opened into them.”15 This conjecture is rendered certain by the fact, that during the dreadful earthquake which happened in the year , not only did the three more remarkable fountains gush forth with uncommon violence, but no less than thirty‐five spouting springs made their appearance, many of which, however, afterwards abated in their fury,16

During the night there had been two large explosions of the Great Geyser, but the servant who observed them not awakening us, we were deprived of the sight. However, the loss was made up by the comfortable sleep we enjoyed, of which we had much need, having been fatigued by the ride, and the walks we took after our arrival the preceding day.

At ten minutes before ten, we were attracted to the mound by several loud reports, which were succeeded by a partial eruption; none ot the jets exceeding five feet in height. About half past ten the reports were reiterated, but no jets ensued; only a gentle rise was observable in p. 53 the contents of the bason. At eleven we were again gratified with a most brilliant eruption. The jets were ten or twelve in number, and the water was carried to the height of at least sixty feet. Vast clouds of steam, which made their escape during the eruption, continued to roll and spread as they ascended, till they filled the whole of the horizon around us; and the sun, though shining in full splendour, was completely eclipsed; but the points of the jets, receiving his rays as they rose through the vapour, wore the most charming lustre, being white and glistening as snow. The instant all was over, Mr. Hodgson and I repaired to the foot of a small cataract, at the northern base of the mound, over which the streamlet is precipitated in its way down to the river, and had a pleasant bath in the warm water as it fell upon us from the rock above.

A small preliminary eruption again took place at seventeen minutes past one, and another four minutes before two. The bason continued filling, till within three minutes of three, when, after a number of very loud reports, the water burst, and the spouts rose with a noise and velocity which I can compare to nothing more aptly than to those of a quantity of large rockets fired off from the same source. This eruption was the longest of any we saw: a space of eight minutes and ten seconds elapsing from the first propulsion of the water from the bason, till it again subsided into the pipe. The jets were also much higher than in any of the former eruptions, p. 54 yet none of them exceeded an hundred feet.

Our two friends now left us, for the purpose of visiting some other hot springs on their return to Reykiavik; but we resolved to spend another night at this place, chiefly for the sake of our horses, that they might be sufficiently rested before we entered the mountains. In the course of the afternoon and evening, there were several indications of a fresh eruption, but they only proved strong ebullitions, which always take place till the bason gets filled. At thirty‐five minutes past nine we had another fine spectacle, which was little inferior to any of the preceding, and lasted for the space of five minutes.

The most enrapturing scene, however, that we beheld, was exhibited on the . About ten minutes past five, we were roused by the roaring of Strockr, which blew up a great quantity of steam; and when my watch stood at the full quarter, a crash took place as if the earth had burst, which was instantaneously succeeded by jets of water and spray, rising in a perpendicular column to the height of sixty feet. As the sun happened to be behind a cloud, we had no expectation of witnessing any thing more sublime than we had already seen; but Strockr had not been in action above twenty minutes, when the Great Geyser, apparently jealous of her reputation, and indignant at our bestowing so much of our time and applause on her rival, began to thunder tremendously, and emitted such

p.

Our attention was so much taken up with these two principal fountains, that we had little time or inclination to watch the minutiae of the numerous inferior shafts and cavities with which p. 57 the tract abounds. The Little Geyser erupted perhaps twelve times in the twenty‐four hours; but none of its jets rose higher than eighteen or twenty feet, and generally they were about ten or twelve. The pipe of this spring opens into a beautiful circular bason about twelve feet in diameter, the surface of which exhibits incrustations equally beautiful with those of the Great Geyser. At the depth of a few feet, the pipe, which is scarcely three feet wide, becomes very irregular; yet its depth has been ascertained to be thirty‐eight feet. There is a large steam‐hole at a short distance, to the north‐west of the Little Geyser, which roars and becomes quiescent with the operations of that spring. A little further down the tract are numerous apertures, some of which are very large, and, being full of clear boiling water, they discover to the spectator the perilous scaffolding on which he stands. When approaching the brink of many of them, he walks over a dome of petrified morass, hardly a foot in p. 58 thickness, below which is a vast boiling abyss, and even this thin dome is prevented from gaining a due consistence, by the humidity and heat to which it is exposed. Near the centre of these holes is situated the Little Strockr, a wonderfully amusing little fountain, which darts its waters in numerous diagonal columns every quarter of an hour.

Nor is it in this direction alone that orifices and cavities abound. In a small gulley close to the Geyser, is a number of holes, with boiling water; to the south of which, rises a bank of ancient depositions, containing apertures of a much larger size than the rest. One of these is filled with beautifully clear water, and discovers to a great depth various groupes of incrustations which are very tempting to the eye of the beholder. The depth of this reservoir is not less than fifty feet. On the brow of the hill, at the height of nearly two hundred feet above the level of the Great Geyser, are several holes of boiling clay; some of which produce sulphur, and the efflorescence of alum; and at the base of the hill, on the opposite side, are not less than twenty springs, which proves that its foundations are entirely perforated with veins and cavities of hot water.

About eleven o’clock, we were under the necessity of lifting our tents, and removing from a place where we had seen some of the grandest of the works of God; and proceeded on to Haukadal, which lies at the distance of three quarters of a mile to the north of the Geysers, and, on account p. 59 of its being the place where Ari Frode, the first historiographer of the north, received his education, has nearly as strong a claim on the attention of the historian as the neighbouring fountains have on that of the naturalist. Ari was one of the most learned Icelanders of his day, and wrote several books of history, the greater part of which have been lost, and all that we now have of his works are the Schedæ and Landnâmabok, the latter of which, was continued by other learned men after his death. He was born in the year , and came to Haukadal in the year , where, in company with Teitr, the son of Bishop Isleif, he long enjoyed the tuition of Hallr hinn Milldi, who is said to have been the most liberal and beneficent man on the island. The present occupant is in good circumstances, and possessed of a very frank and obliging disposition. He conducted us into the house, which is uncommonly orderly and clean, and felt no small degree of pleasure in relating to us the different foreign guests that had visited him. He purchased a copy of the New Testament, as did also a young man in the vicinity of the Geysers.

As we had rode on about half an hour before our baggage horses, we went a little to the west of Haukadal, to see the remains of St. Martin’s bath. On the eastern brink of the small river which intersects the plain, is a large stone, eight feet in length, by about five in diameter, the one end of which projecting into the water, contains p. 60 a small hole about twice the size of a man’s hand, through which boiling water issued about twenty years ago. It is now quite dry, and in a great measure filled up with minute depositions which have been left on the subsiding of the water. Forty years ago, there was another sharp point attached to the stone, in which was a pipe conveying cold water to the bath, which was situated below the projection, so that those who bathed had it in their power to cool or heat the bath at pleasure, by opening either of the cocks fixed in the pipes. The hot water still issues forth in the middle of the river. In the days of ignorance and superstition, this bath was supposed to possess miraculous powers; and numbers resorted to it from various parts, in order to find relief from the diseases with with which they were afflicted.

The general appearance of the intervening ground between the Geysers and Haukadal plainly indicates, that, in former times, it also has been the seat of hot springs. Indeed, the whole tract consists of a stream of lava that has flowed down into the plain from some of the mountains to the north of Haukadal, and which appears, on advancing as far as the Geysers, to have stopped, and thrown up the mountain called Laugafell, at the base of which these springs are situated. When we consider the remoteness of the period at which this must have happened, it appears truly surprising that subterraneous heat should still exist, in the degree necessary p. 61 to account for the stupendous operations of the springs, while it has never so far accumulated as to produce a volcanic eruption.18

p. 62Our way now lay over a considerable portion of this lava, which was for the most part covered with heath, but every now and then presented springs from which a large quantity of cold chrystalline water issued into the plain. The surface also exhibited in many places, bushes of willow and birch, but scarcely ever of that size to entitle them to the name of underwood. On crossing Fliotsâ, a broad but shallow river, we came to a hamlet called Holum, where, as it was the last house on this side of the desert, we regaled ourselves with a plentiful draught of cream. The family, which was numerous, looked exceedingly poor; and, as they had only an old defective copy of the second part of the Old p. 63 Testament, I gave the children a copy of the New, in the hopes that the uncommonness of the gift might excite attention to its contents. Their mother immediately summoned them to give me a kiss, in token of their thankfulness for the boon. I now requested them to read a little, when the youngest girl, who might be about fourteen years of age, performed her task with much propriety, though somewhat intimidated by the presence of strangers. She then handed the Testament to her sister, who was upwards of eighteen, and read with so sonorous a voice, that two hundred people might have heard her with ease. It was pleasing to observe, from her manner, and the emphasis she laid on the proper words, that she not only understood, but seemed to feel the importance of what she read. It was part of the evangelic history of the sufferings of the Redeemer.19 After making a remark or two on the importance of the Holy Scriptures, and the necessity of perusing them with diligence, we proceeded on our journey, followed by the blessings of a grateful family.

We pursued our course nearly in any easterly direction, across a desert of deep sand, which proved very fatiguing to our horses, till we arrived p. 64 at the banks of the Hvitâ, or White River, which we found flowing in a serpentine course, now spreading its waters over an extensive sandy bed, and now confined to a narrower channel between walls of columnar rock. We rode along the western bank, till we came to the vicinity of the Blue Mountain (Blâfell), when we struck off to the left, and encamped about seven in the evening, at a short distance from the base of the mountain. Our station consisted of a sandy hill, partially overgrown with moss, coarse grass, and a few dwarfy willows, close to a rivulet which falls into the Hvitâ, a little farther down. Directly behind us rose the huge extinct volcano of Blâfell, the summit of which was enveloped in mist, and its sides, which were entirely destitute of vegetation, presented, in many places, deep ravines filled with snow. At a considerable distance towards the west, we could descry the fantastic summits of a long range of volcanic hills: while, in an easterly direction, the eye was carried over an extensive plain, bounded in the distance by the chain of mountains to the north of Hekla, which, at that time, was free from smoke and flames, and only distinguishable by the mantle of snow, from which she derives her name. Our situation appeared gloomy in the extreme; but, after kindling a fire, and partaking of some refreshment, we retired to rest, and soon buried in sleep all the unpleasant reflections occasioned by the prospect of the desert.

p. 65, we assembled in Captain Von Scheel’s tent, when one of the servants read the third and fourth chapters of the Gospel by John, in Icelandic; after which we were under the necessity of prosecuting our journey, the horses having eaten all the grass in the vicinity during the night, and we had a ride of more than thirty miles to the next station. During the first three hours, we had rather a tedious ride up the steep ascent covered with broken lava, which extends along the west side of the mountain, till we gained its summit, called Blâfells‐hâls, where there is a passage between that mountain and the immense chain of ice‐mountains in the interior. From this elevation we had a most commanding prospect of the whole level tract of country, which, beginning at Haukadal, and stretching past Skalholt, opens into the extensive plains between mount Hekla and the sea. Several miles behind Thingvalla, lay the large volcanic mountains called Skialdbreid and Tindafiall; and between us and this latter mountain, a regular chain of high conical mountains commenced, which stretched to a considerable distance along the base of the neighbouring Yökul. The blackness of their appearance formed a perfect contrast to the whiteness of the perennial snows behind them. What particularly struck us, was the majesty of the vast ice mountain, which extends from a little to the east of Tindafiall, in a westerly and northerly direction, to the distance of not less p. 66 than an hundred miles across the interior of the island. Though forming but one connected mass of ice and snow, it is divided into four parts in the geographical descriptions. The south‐east division, which lay next us, is known by the name of Blâfells‐Yökul: a little farther north it assumes the name of Eiriks‐Yökul; and the most northerly is called Bald‐Yökul. The fourth division is that of Geitlands‐Yökul, which terminates the mountain to the west, and stretches along the north‐east parts of the Syssel of Borgarfiord. At the spot on which we now stood, it was in our power to receive strong mental impressions either of heat or cold, according to the direction in which we turned. When we looked to the west and north, we had nothing before us but regions of ever‐during ice; whereas, on turning to the south, we were reminded by the clouds of smoke ascending from the Geysers, of the magazines of fire that lay concealed in that neighbourhood.

Descending by the west end of Blâfell, which here consists of immense irregular masses of dark brown tuffa, we came again, in the course of a short time, to the Hvitâ, near its egress from a large lake, to which it gives the name of Hvitârvatn. The whole of the western margin of this lake is lined with magnificent glaciers, which, before meeting the water, assume a hue of the most beautiful green. It abounds with excellent fish, and used to be much frequented in former times by the peasants in the south. At the fording‐place, p. 67 the river may be about an hundred yards across; and we found it in some places so deep, that our horses were on the point of swimming. It is certainly the most formidable river in this quarter of Iceland; and is often unfordable for weeks together, when travellers, coming from the desert, are not unfrequently reduced to great straits, by the consumption of the food they had provided for their journey.

On leaving the Hvitâ, we encountered a long tract of volcanic sand, with here and there insulated stones, of an immense size, which must have been erupted from the Kerlingar‐fialla volcanoes, situated at the distance of fifteen or twenty miles in an easterly direction. Most of these volcanic mountains form beautiful pyramids; and some of them are of a great height, and partially covered with snow. The cone, in the remote distance, is most perfectly formed, and is quite red in appearance, arising from the scoriae deposited on its sides. None of these volcanoes have ever been explored; nor have I so much as met with their names in any description of the island that I have seen. From the peasant at Holum, who has proceeded several times to the vicinity in search of moss, I learned that a very extensive tract of lava stretches between them and the ancient road, called Spreingi‐sand; and at one place he observed much smoke, which he supposed arose from springs of boiling water.

At four o’clock we came to the Black River (Svartâ), fording which, we fell in with an p. 68 extensive tract, known by the name of the Kialhraun, which has been at least twice subjected to fiery torrents from a volcano in the neighbourhood of Bald‐Yökul, if not from the Yökul itself. This lava is upwards of twenty miles in length; and, in some places, five or six in breadth. Here the road divided: that called Kialvegur, leading to Skagafiord, lay to the left, across the lava; whereas the way to Eyafiord, which we pursued, ran along its eastern margin, now on one side of the Black River, and now on the other. After travelling about eight miles farther, over a very stony tract, we came to the station of Grânaness, which we found to be the termination of a very ancient stream of lava, mostly covered with moss and willows, and having only a little grass in the cavities, which have been formed by the bursting or falling in of the crust. Inhospitable as it appeared, we were obliged to stop, as we were exposed to a heavy rain, and the next green spot was about fifty miles distant.

On the afternoon of , we commenced the worst stage on our whole journey. Our road, which at times was scarcely visible, lay along the west side of the Hof, or Arnarfell Yökul, a prodigious ice mountain, stretching from the volcanoes above mentioned, in a northerly direction, for upwards of fifty miles, when it turns nearly due east, and extends to nearly thirty miles in that direction. The appellation of Langi Yökul is also given to p. 69 this mountain on the maps, but improperly, as that designation exclusively belongs to the extensive chain of ice mountains already described, as known by the subdivisions of Blâfell, Geitland, Eirik, and Bald Yökuls. On passing it, however, we certainly found it sufficiently long: for we rode at no great distance from it for the space of twenty hours, and were all the time exposed to a cold piercing wind which blew from that quarter. About eleven at night we came to the Blanda, or Mixed River, the waters of which were of a bluish colour, and, dividing into upwards of a dozen of branches, they rendered our passage both tedious and troublesome. Near the north‐west corner of the Yökul, a great number of curiously shaped hills presented themselves to our view, which we found, on approaching them, to be partly volcanic, and partly immense masses of Yökul, intermixed with drosses and fragments of lava, which have been separated from the mountain during some of its convulsions, and hurled along to their present situation by the inundations it has poured down upon the plains. At , as we had got quite surrounded by these hills, and were almost shivering with cold (the waters being covered with fresh ice), we were gratified with a view of the sun, rising in all his glory directly before us. The gloom in which we had been involved now fled away; and we obtained a very extensive prospect of the surrounding country. It was a p. 70 prospect, however, by no means pleasing; for to whatever side we turned, nothing was visible but the devastations of ancient fires, or regions of perpetual frost:

――Pigris ubi nulla campis

Arbor aestivâ recreatur aurâ.

We were not only far from the habitations of men, but deserted even by the beasts of the field, and the birds of the air. Here “no voice of cattle is ever heard: both the fowl of the heavens and the beast are fled; they are gone.”20

Leaving a region “where all life dies, death lives, and nature breeds perverse, all monstrous, all prodigious things,” we entertained the hope of meeting soon with a more enlivening prospect. In this, however, we were disappointed: for, we had advanced only a short way, when we entered a stream of lava, which we found rugged and wild in the extreme, and which it took us near an hour to cross. Deep ravines and chasms presented themselves in every quarter; and in many places were huge blisters, full of cracks, which the raging element has formed in its progress. The idea of a fiery torrent, nearly two miles in breadth, proceeding from an ice mountain, will appear to many the wildest and most incongruous that can possibly be conceived: yet such, in reality, was the fact now exhibited before us. p. 71 We could evidently see the stream of lava descending from the Yökul, at the distance of about a mile to our right, and pursuing its course in a westerly direction among numerous small conical hills, which it has thrown up as it advanced. This lava is called the Lamba‐hraun, from the circumstance of a number of lambs having been once found in it.

Our way lay next across several considerable hills of yellowish tuffa, with here and there appearances of lava, assuming a basaltine configuration. About nine in the morning we halted at a small green spot, nearly five miles to the north of Illvidris‐hniukar, a number of variously shaped volcanic hills, which, at a very remote period, have poured forth burning streams to a great distance on the north side of the Yokul; but, finding the grass insufficient for the following night, we set off again about three o’clock in the afternoon, and travelled upwards of eight miles over barren stony mountains, till we arrived at the Yökulsâ, or the River of the Ice Mountains, which flowed with great rapidity in a deep channel, the banks of which were composed of clay and loose earth, and on this account very difficult of descent. The fording of this river is attended with considerable danger, owing to the large stones at the bottom, which the traveller is prevented from seeing by the muddiness of the water. In fording it, my horse stumbled with me three times, and had nearly precipitated me into the stream: but the Lord p. 72 preserved me, and caused me to experience the literal fulfilment of that gracious promise: “When thou passest through the waters, I will be with thee, and through the rivers, they shall not overflow thee.”21 Having ascended the northern bank, we came to a tract of marshy ground, where we pitched our tents, and retired immediately to sleep, being much fatigued with the long ride.

Before reaching this part of the desert, we had been rather alarmed by the appearance of two rivers on the maps, which, from their size as there delineated, wore as formidable an aspect as any on the island. They are described as taking their rise from some common source to the south‐east of Arnarfells‐Yökul; and, after separating, the one pursues its course down Öxnadal, and pours its waters into the bay of Eyafiord, and the other runs past Holum into the Skagafiord. But no such rivers appear ever to have existed. The Yökul River, we had just forded, is the only river of any consequence to the north of the Yökul; and the Öxnadal and Kolbeinsdal rivers are by no means of the size laid down on the maps, and take their rise in the mountains, between the coast and Vatna‐hialli, the name by which the desert tract to the north of the Yökul is designated.

At eight o’clock, on the , we renewed our journey across the mountains. p. 73 The road was very rough and unbeaten, and mostly up‐hill till about noon, when we gained the summit of the mountain‐pass, and began to descend on the other side. The descent was at first exceedingly stony and precipitous, and in many places we could not discover any tract. There were, however, heaps of stones cast up at various distances to point out the way, and in some places a heap of bones, from which we could conclude, that the horses of some former travellers had fallen a sacrifice to the badness of the road, while it at the same time warned us of the danger to which our own were exposed. After travelling over several wreaths of snow, and descending about two miles, we could discern from the rise of the mountains before us, that we approached the valley of Eyafiord. Having proceeded about two miles farther, we came to the side of a wide and deep gulley, which the mountain‐torrent had made in its way down to the valley. The road now lay along the south side of this gulley, in a zig‐zag direction, but was nevertheless so precipitous, and approached at times so near the fissure, that if we had rode on any other but Icelandic horses, we certainly could not have ventured where we did. The change in the prospect was indescribably delightful. The green grass with which the valley was richly clad, the beautiful river by which it was intersected, the cottages which lay scattered on both sides, and the sheep and lambs which were grazing in every direction, and which, from their p. 74 distance below us, appeared only as small specks; these circumstances, combined with the height of the mountains that boldly faced each other, and then sloped gently down into the valley, proved an agreeable relief to the eye, which for four days had scarcely beheld a tuft of grass, or indeed any thing but stones and snow. Our very horses seemed to be animated with the prospect before them, and mended their pace of their own accord. At half past two, we arrived at the foot of the descent, which altogether could not be less than two thousand five hundred feet.

As our baggage horses did not make their appearance on the heights behind us, we allowed our horses to feast on the luxuriant grass in the valley, while we entered the gulley in order to view the scenery. A little way up it opens most majestically on the view, being divided by the torrent into two semicircles, and the cliffs, which surround the opening at the height of between four and five hundred feet, rising into beautiful domes and turrets of various sizes. It resembled a vast amphitheatre, and inspired the mind with sentiments of wonder and awe.

On returning from the fissure, we were surprised to find that the men and horses had not yet arrived, and began to entertain suspicions lest some evil had befallen them on the mountain; but after some time, we discovered them proceeding along the opposite side of the valley, having descended by another road, though neither p. 75 so near, nor so easy of descent as that which we had taken.

We now made the best of our way to the first farm in the valley, which is called Tiörnabæ, and lay at a little distance before us. It is situated exactly in the middle of the valley, upon a beautiful green mount, and consists of several houses which lie together in a cluster, besides smaller ones for the cattle at a short distance from each other. In general, the Icelandic houses are all constructed in the same manner, and, with little or no variation, exhibit the plan of those raised by the original settlers from Norway. The walls, which may be about four feet in height by six in thickness, are composed of alternate layers of earth and stone, and incline a little inwards, when they are met by a sloping roof of turf, supported by a few beams which are crossed by twigs and boughs of birch. The roof always furnishes good grass, which is cut with the scythe at the usual season. In front, three doors generally present themselves, the tops of which form triangles, and are almost always ornamented with vanes. The middle door opens into a dark passage, about thirty feet in length, by five in breadth, from which entrances branch off on either side, and lead to different apartments, such as, the stranger’s room, which is always the best in the house, the kitchen, weaving room, &c. and at the inner end of the passage lies the Badstofa, or sleeping apartment, which also forms the sitting and common working‐room p. 76 of the family. In many houses this room is in the garret, to which the passage communicates by a dark and dangerous staircase. The light is admitted through small windows in the roof, which generally consist of the amnion of sheep, though of late years glass has got more into use. Such of the houses as have windows in the walls, bear the most striking resemblance to the exterior of a bastion. The smoke makes its escape through a hole in the roof; but this, it is to be observed, is only from the kitchen, as the Icelanders never have any fire in their sitting‐room, even during the severest cold in winter. Their beds are arranged on each side of the room, and consist of open bedsteads raised about three feet above the ground. They are filled with sea weed, feathers, or down, according to the circumstances of the peasant; over which is thrown a fold or two of wadmel, and a coverlet of divers colours. Though the beds are extremely narrow, the Icelanders contrive to sleep in them by couples, by lying head to foot. Sometimes the inside of the rooms are pannelled with boards, but generally the walls are bare, and collect much dust, so that it is scarcely possible to keep any thing clean. It is seldom the floor is laid with boards, but consists of damp earth, which necessarily proves very unhealthy.

In the stranger’s room is a long table with a parallel bench, next to the wall on the one side, and the place of chairs is commonly supplied on the other by large chests, containing the clothes, p. 77 valuables, &c. of the inhabitants. From the ceiling are also suspended numerous habiliments, and articles of domestic economy; and in some houses, a bed is put up here with curtains, for the accommodation of travellers. Foreigners always complain of the insupportable stench and filth of the Icelandic houses, and, certainly, not without reason; yet I question much if these evils do not exist nearly in the same degree in the Highlands of Scotland, the country hamlets of Ireland, or the common Bauer huts in Germany.

One of the side doors in front, opens into what is called the Skemma, a separate apartment containing dried fish and other winter‐stores, riding accoutrements, &c. Otherwise this name seems originally to have denoted a gynæceum, which was solely occupied by the female part of the family. The other door is that of the smithy, which, however, in some parts of the island, stands by itself. To these are appended several smaller out‐houses for the reception of the cows, and, at a short distance, are those appropriated for the sheep. The whole, together with the hay stacks in the yard, forms a group not altogether unpleasant to the eye of the traveller on approaching it.

The numerous flocks of sheep which surrounded Tiörnabæ, convinced us that the peasant was in good circumstances. On riding up to the door he came out to us, and after learning who we were, he conducted us, with looks of kindness, p. 78 into the best room in the house, and immediately provided us with cream to quench our thirst till his wife got something prepared for us to eat. In the meantime, our servants fixed the tents at the back of the house. On learning that I had Bibles with me, the peasant, who is a young man, and newly married, regretted that he had not been able, as yet, to furnish his house with a copy, and expressed a wish to see one of those I had in my trunks. Having taken a Bible and a New Testament to shew his wife, he soon returned, having resolved to take both, and paid the price with the utmost cheerfulness. I had scarcely turned to re‐enter my tent, when two servant girls came running with money in their hands, and wished to have each a New Testament. As my stock was small, and I had a considerable extent of country to supply from it, chiefly as samples, I was sorry I was under the necessity of putting them off till next year, but testified my approbation of their wish to possess the word of God; and begged them to read, in the mean time, the copies that had come into the family.

Taking into consideration the remoteness of the surrounding cottages from the nearest market‐place to which it was intended to forward Bibles next year, I sent for two of the poorest people in the vicinity, and gave each of them a Testament. One of them had a Danish Bible, which he endeavoured, as well as he could, to collect the sense of, but he understood the language very p. 79 imperfectly. He thanked me repeatedly, with tears in his eyes, and rode home quite overjoyed at the gift he had received. The other, a young man about nineteen, had been dispatched by his poor and aged parents, to learn the truth of the message that had been sent them. There was an uncommon degree of humble simplicity in his countenance. On receiving the Testament, it was hardly possible for him to contain his joy. As a number of people had now collected round the door of my tent, I caused him to read the third chapter of the Gospel of John. He had scarcely begun, when they all sat down, or knelt on the grass, and listened with the most devout attention. As he proceeded, the tears began to trickle down their cheeks, and they were all seemingly much affected. The scene was doubtless as new to them as it was to me; and, on my remarking, after he had done, what important instructions were contained in the portion of Scripture he had read, they gave their assent, adding, with a sigh, that they were but too little attended to. The landlady especially seemed deeply impressed with the truths she had heard, and remained sometime after the others were gone, together with an aged female, who every now and then broke out into exclamations of praise to God, for having sent “his clear and pure word” among them. It is impossible for me to describe the pleasure I felt on this occasion. I forgot all the fatigues of travelling over p. 80 the mountains; and, indeed, to enjoy another such evening, I could travel twice the distance. I bless God for having counted me worthy to be employed in this ministry; to dispense his holy word among a people prepared by him for its reception, and to whom, by the blessing of his Spirit, it shall prove of everlasting benefit: nor can I be sufficiently thankful to the Committee of the British and Foreign Bible Society for having constituted me the almoner of their bounty, and sending me on an errand, which, while it brings felicity to others, proved a source of so much enjoyment to my own mind.

we pursued our route down the valley. The ride was the most agreeable imaginable. The valley is well inhabited, being covered with luxuriant verdure, and affording an excellent pasturage to the sheep and cattle, which form the principal riches of the Iceland peasant. The mountains by which it is sheltered on both sides, are between 3000 and 4200 feet in height; and are clad with grass more than half way up to the summit. The cottages looked far superior to those in the south, and the churches, several of which we passed, had also a more decent appearance. In that of Grund, which we surveyed while the peasant was getting our horses ready, I was surprised to find an old portrait of General Monk hanging on the wall, to the right of the altar, with a few acrostic lines, savouring strongly of p. 81 the times in which they were written. How it came here is more than I could learn.

On the right hand side of the valley, we could observe Nupufell, famous for its having been the seat of the Icelandic printing press, which Bishop Gudbrand improved on his being installed into the see of Holum. Jon Jonson, whose father had brought the original press from Sweden about the year , was prevailed upon by the Bishop to undertake a voyage to Copenhagen, in order to acquire a more perfect knowledge of the art, and, on his return, received this farm as a perpetual residence for hintself and his successors in office; but the Bishop soon found the place inconvenient, on account of the distance, and got the press removed to Holum, where he rendered the establishment more complete.22 On the same side of the valley lay Thverâ Abbey, which was erected by Biörn, Bishop of Holum, in the year , and governed according to the rules of the Benedictine monks, by a series of five and twenty abbots, till the time of the Reformation, when it was secularised along with the other monasteries and abbeys on the island.23

A little farther on, we came to Hrafnagil, the residence of the very Rev. Magnus Erlandson, Dean of the Eyafiord district. On delivering a p. 82 letter to him, which I had from the Bishop, he kindly told me, that, independent of the Bishop’s recommendation, I should have found him ready to lend me all the assistance in his power, in the promotion of the good work in which I was engaged; and as he was to commence his autumnal visitation the day following, he promised to inform the clergy of his district of the new edition of the Scriptures, and request them to institute an inquiry into the state of their parishes with respect to Bibles, that the necessary quantity of copies might be sent to this quarter.

About four o’clock we arrived at the factory of Akur‐eyri, where I was conducted by Captain Von Scheel into his house, and introduced to his lady, who, with her husband, strove to procure me all the comforts necessary for my refreshment, after so fatiguing a journey.

Akur‐eyri, or, as it is called in Danish, Oefiord, is one of the principal trading stations on the northern coast of Iceland. It is situated on the west side of the Eyafiord bay, and consists of three merchants’ houses, several storehouses and cottages, amounting in all to about eighteen or twenty. The trade is “much the same with that of the other stations,” consisting chiefly in bartering rye and other articles of foreign produce for wool, woollen goods, salted mutton, &c. It was formerly famous for its herring‐fishery; the herrings frequenting the bay in such quantities, that between 180 and 200 barrels have been caught at a single draught; but they have of p. 83 late years almost entirely disappeared, to the no small disadvantage of the peasantry in the district, who were furnished with them at the rate of a rixdollar per barrel. The Danish officers, Captain Von Scheel, and Captain Frisac, have resided here with their families during the time they have been in Iceland. The latter gentleman had just sailed with his family for Copenhagen, and Captain Von Scheel intended also sailing with his, by a vessel lying in the bay. There is a small garden or two attached to several of the houses; but the proper gardens lie behind the town, on the face of a hill, where they have an excellent southern exposure. They produce chiefly cole‐rape and potatoes. The latter article came in season while I was at the place, which was considered very early in Iceland.