Website Search

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

In this class is properly comprised those fictions which, with some variations, are told at the domestic gatherings of Celts, Teutons, and Slavonians, and are more distinguished by a succession of wild and wonderful adventures than a carefully‐constructed framework. A dramatic piece exhibiting reflection, and judgment, and keen perception of character, but few incidents or surprises, may interest an individual who peruses it by his fireside, or as he saunters along a sunny river bank; but let him be one of an audience witnessing its performance, and he becomes sensible of an uncomfortable change. Presence in a crowd produces an uneasy state of expectation, which requires something startling or sensational to satisfy it. Thus it was with the hearth‐audiences. It needed but few experiments to put the first story‐tellers on the most effective way of amusing and interesting the groups gathered round the blaze, who for the moment felt their mission to consist in being agreeably excited, not in applying canons of criticism.

p. 4The preservation of these tales by unlettered people from a period anterior to the going forth of Celt or Teuton or Slave from the neighbourhood of the Caspian Sea is hard to be accounted for. The number of good Scealuidhes dispersed through the country parts is but small compared to the mass of the people, and hundreds may be found who recollect the succession of events and the personages of a tale while utterly incapable of relating it.

In remote neighbourhoods, where the people have scarcely any communication with towns or cities, or access to books, stories will be heard identical with those told in the Brothers Grimm’s German collection, or among the Norse tales gathered by MM. Asbjornsen and Moë. We cannot for a moment imagine an Irishman of former days speaking English or his native tongue communicating these household stories to Swede or German who could not understand him, or suppose the old dweller in Deutschland doing the good office for the Irishman. The ancestors both of Celt and Teuton brought the simple and wonderful narratives from the parent ancestral household in Central Asia. In consideration of the preference generally given by young students to stirring action rather than dry disquisition, we omit much we had to say on the earliest forms of fiction, and introduce a story known in substance to every Gothic and Celtic people in Europe. It is given p. 5 in the jaunty style in which we first heard it from Garrett (Gerald) Forrestal of Bantry, in Wexford.

Once there was a poor widow, and often there was, and she had one son. A very scarce summer came, and they didn’t know how they’d live till the new potatoes would be fit for eating. So Jack said to his mother one evening, “Mother, bake my cake, and kill my cock, till I go seek my fortune; and if I meet it, never fear but I’ll soon be back to share it with you.” So she did as he asked her, and he set out at break of day on his journey. His mother came along with him to the bawn (yard) gate, and says she,—“Jack, which would you rather have, half the cake and half the cock with my blessing, or the whole of ’em with my curse?” “O musha, mother,” says Jack, “why do you ax me that question? sure you know I wouldn’t have your curse and Damer’s1 estate along with it.” “Well, then, Jack,” says she, “here’s the whole tote (lot) of ’em, and my thousand blessings along with them.” So she stood on the bawn ditch (fence) and blessed him as far as her eyes could see him.

Well, he went along and along till he was tired, and ne’er a farmer’s house he went into wanted a boy.2 At last his road led by the side of a bog, and there was a poor ass up to his shoulders near a big bunch of grass he was striving to come at. “Ah, then, Jack asthore,” says he, “help me out or I’ll be dhrounded.” “Never say’t twice,” says Jack, and he pitched in big stones and scraws (sods) into the slob, till the ass got good ground p. 6 under him. “Thank you, Jack,” says he, when he was out on the hard road; “I’ll do as much for you another time. Where are you going?” “Faith, I’m going to seek my fortune till harvest comes in, God bless it!” “And if you like,” says the ass, “I’ll go along with you; who knows what luck we may have!” “With all my heart; it’s getting late, let us be jogging.”

Well, they were going through a village, and a whole army of gorsoons3 were hunting a poor dog with a kittle tied to his tail. He ran up to Jack for protection, and the ass let such a roar out of him, that the little thieves took to their heels as if the ould boy (the devil) was after them. “More power to you, Jack!” says the dog. “I’m much obleeged to you: where is the baste4 and yourself going?” “We’re going to seek our fortune till harvest comes in.” “And wouldn’t I be proud to go with you!” says the dog, “and get shut (rid) of them ill conducted boys; purshuin’ to ’em!” “Well, well, throw your tail over your arm, and come along.”

They got outside the town, and sat down under an old wall, and Jack pulled out his bread and meat, and shared with the dog; and the ass made his dinner on a bunch of thistles. While they were eating and chatting, what should come by but a poor half‐starved cat, and the moll‐row he gave out of him would make your heart ache. “You look as if you saw the tops of nine houses since breakfast,” says Jack; “here’s a bone and something p. 7 on it.” “May your child never know a hungry belly!” says Tom; “it’s myself that’s in need of your kindness. May I be so bold as to ask where yez are all going?” “We’re going to seek our fortune till the harvest comes in, and you may join us if you like.” “And that I’ll do with a heart and a half,” says the cat, “and thank’ee for asking me.”

Off they set again, and just as the shadows of the trees were three times as long as themselves, they heard a great cackling in a field inside the road, and out over the ditch jumped a fox with a fine black cock in his mouth. “Oh you anointed villian!” says the ass, roaring like thunder. “At him, good dog!” says Jack, and the word wasn’t out of his mouth when Coley was in full sweep after the Moddhera Rua (Red Dog). Reynard dropped his prize like a hot potato, and was off like shot, and the poor cock came back fluttering and trembling to Jack and his comrades. “O musha, naybours!” says he, “wasn’t it the hoith o’ luck that threw you in my way! Maybe I won’t remember your kindness if ever I find you in hardship; and where in the world are you all going?” “We’re going to seek our fortune till the harvest comes in; you may join our party if you like, and sit on Neddy’s crupper when your legs and wings are tired.”

Well, the march began again, and just as the sun was gone down they looked around, and there was neither cabin nor farm house in sight. “Well, well,” says Jack, “the worse luck now the better another time, and it’s only a summer night after all. We’ll go into the wood, and make our bed on the long grass.” No sooner said than done. Jack stretched himself on a bunch of dry grass, the ass lay near him, the dog and cat lay in the ass’s warm lap, and the cock went to roost in the next tree.

Well, the soundness of deep sleep was over them all, when the cock took a notion of crowing. “Bother you, Cuileach Dhu (Black Cock)!” says the ass: “you p. 8 disturbed me from as nice a wisp of hay as ever I tasted. What’s the matter?” “It’s daybreak that’s the matter: don’t you see light yonder?” “I see a light indeed,” says Jack, “but it’s from a candle it’s coming, and not from the sun. As you’ve roused us we may as well go over, and ask for lodging.” So they all shook themselves, and went on through grass, and rocks, and briars, till they got down into a hollow, and there was the light coming through the shadow, and along with it came singing, and laughing, and cursing. “Easy, boys!” says Jack: “walk on your tippy toes till we see what sort of people we have to deal with.” So they crept near the window, and there they saw six robbers inside, with pistols, and blunderbushes, and cutlashes, sitting at a table, eating roast beef and pork, and drinking mulled beer, and wine, and whisky punch.

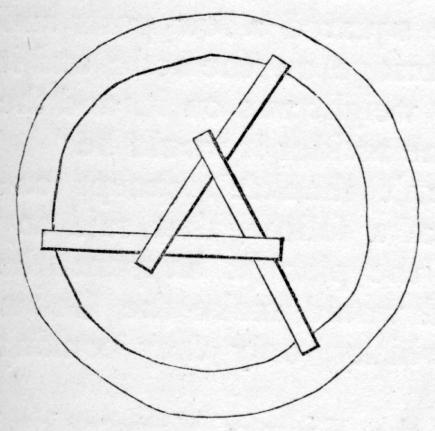

“Wasn’t that a fine haul we made at the Lord of Dunlavin’s!” says one ugly‐looking thief with his mouth full, “and it’s little we’d get only for the honest porter: here’s his purty health!” “The porter’s purty health!” cried out every one of them, and Jack bent his finger at his comrades. “Close your ranks, my men,” says he in a whisper, “and let every one mind the word of command.” So the ass put his fore‐hoofs on the sill of the window, the dog got on the ass’s head, the cat got on the dog’s head, and the cock on the cat’s head. Then Jack made a sign, and they all sung out like mad. “Hee‐haw, hee‐haw!” roared the ass; “bow‐wow!” barked the dog; “meaw‐meaw!” cried the cat; “cock‐a‐doodle‐doo!” crowed the cock. “Level your pistols!” cried Jack, “and make smithereens of ’em. Don’t leave a mother’s son of ’em alive; present, fire!” With that they gave another halloo, and smashed every pane in the window. The robbers were frightened out of their lives. They blew out the candles, threw down the table, and skelped out at the back door as if they were in earnest, and never drew rein till they were in the very heart of the wood.

p. 9Jack and his party got into the room, closed the shutters, lighted the candles, and ate and drank till hunger and thirst were gone. Then they lay down to rest;—Jack in the bed, the ass in the stable, the dog on the door mat, the cat by the fire, and the cock on the perch.

At first the robbers were very glad to find themselves safe in the thick wood, but they soon began to get vexed. “This damp grass is very different from our warm room,” says one; “I was obliged to drop a fine pig’s crubeen (foot),” says another; “I didn’t get a tay‐spoonful of my last tumbler,” says another; “and all the Lord of Dunlavin’s goold and silver that we left behind!” says the last. “I think I’ll venture back,” says the captain, “and see if we can recover anything.” “That’s a good boy!” said they all, and away he went.

The lights were all out, and so he groped his way to the fire, and there the cat flew in his face, and tore him with teeth and claws. He let a roar out of him, and made for the room door, to look for a candle inside. He trod on the dog’s tail, and if he did, he got the marks of his teeth in his arms, and legs, and thighs. “Millia murdher (thousand murders)!” cried he; “I wish I was out of this unlucky house.” When he got to the street door, the cock dropped down upon him with his claws and bill, and what the cat and dog done to him was only a flay‐bite to what he got from the cock. “Oh, tattheration to you all, you unfeeling vagabones!” says he, when he recovered his breath; and he staggered and spun round and round till he reeled into the stable, back foremost, but the ass received him with a kick on the broadest part of his small clothes, and laid him comfortably on the dunghill. When he came to himself, he scratched his head, and began to think what happened him; and as soon as he found that his legs were able to carry him, he crawled away, dragging one foot after another, till he reached the wood.

“Well, well,” cried them all, when he came within p. 10 hearing, “any chance of our property?” “You may say chance,” says he, “and it’s itself is the poor chance all out. Ah, will any of you pull a bed of dry grass for me? All the sticking‐plaster in Inniscorfy (Enniscorthy) will be too little for the cuts and bruises I have on me. Ah, if you only knew what I have gone through for you! When I got to the kitchen fire, looking for a sod of lighted turf, what should be there but a colliach (old woman) carding flax, and you may see the marks she left on my face with the cards. I made to the room door as fast as I could, and who should I stumble over but a cobbler and his seat, and if he did not work at me with his awls and his pinchers you may call me a rogue. Well, I got away from him somehow, but when I was passing through the door, it must be the divel himself that pounced down on me with his claws, and his teeth, that were equal to sixpenny nails, and his wings—ill luck be in his road! Well, at last I reached the stable, and there, by way of salute, I got a pelt from a sledge‐hammer that sent me half a mile off. If you don’t believe me, I’ll give you leave to go and judge for yourselves.” “Oh, my poor captain,” says they, “we believe you to the nines. Catch us, indeed, going within a hen’s race of that unlucky cabin!”

Well, before the sun shook his doublet next morning, Jack and his comrades were up and about. They made a hearty breakfast on what was left the night before, and then they all agreed to set off to the castle of the Lord of Dunlavin, and give him back all his gold and silver. Jack put it all in the two ends of a sack, and laid it across Neddy’s back, and all took the road in their hands. Away they went, through bogs, up hills, down dales, and sometimes along the yalla high road, till they came to the hall door of the Lord of Dunlavin, and who should be there, airing his powdered head, his white stockings, and his red breeches, but the thief of a porter.

He gave a cross look to the visitors, and says he to p. 11 Jack, “What do you want here, my fine fellow? there isn’t room for you all.” “We want,” says Jack, what I’m sure you haven’t to give us—and that is, common civility.” “Come, be off, you lazy geochachs (greedy strollers)!” says he, “while a cat ’ud be licking her ear, or I’ll let the dogs at you.” “Would you tell a body,” says the cock that was perched on the ass’s head, “who was it that opened the door for the robbers the other night?” Ah! maybe the porter’s red face didn’t turn the colour of his frill, and the Lord of Dunlavin and his pretty daughter, that were standing at the parlour window unknownst to the porter, put out their heads. “I’d be glad, Barney,” says the master, “to hear your answer to the gentleman with the red comb on him.” “Ah, my lord, don’t believe the rascal; sure I didn’t open the door to the six robbers.” “And how did you know there were six, you poor innocent?” said the lord. “Never mind, sir,” says Jack, “all your gold and silver is there in that sack, and I don’t think you will begrudge us our supper and bed after our long march from the wood of Athsalach (muddy ford).” “Begrudge, indeed! Not one of you will ever see a poor day if I can help it.”

So all were welcomed to their heart’s content, and the ass, and the dog, and the cock got the best posts in the farmyard, and the cat took possession of the kitchen. The lord took Jack in hands, dressed him from top to toe in broadcloth, and frills as white as snow, and turn‐pumps, and put a watch in his fob. When they sat down to dinner, the lady of the house said Jack had the air of a born gentleman about him, and the lord said he’d make him his steward. Jack brought his mother, and settled her comfortably near the castle, and all were as happy as you please. The old woman that told me the story said Jack and the young lady were married; but if they were, I hope he spent two or three years getting the edication of a gentleman. I don’t think that a country boy would feel comfortable, striving to find discoorse for a well‐bred young lady, the length of a summer’s day, even p. 12 if he had the “Academy of Compliments,”5 and the “Complete Letter Writer” by heart.

Our archæologists, who are of opinion that beast worship prevailed in Erin as well as Egypt, cannot but be well pleased with our selection of this story, seeing the domestic animals endowed with such intelligence, and acting their parts so creditably in the stirring little drama. This animal cultus must have been of a fetish character, for among the legendary remains we find no acts of beneficence ascribed to serpent, or boar, or cat, but the contrary. The number of places in the country named from animals is very great. A horse cleared the Shannon at its mouth (a leap of nine miles); one of the Fenian hounds sprung across the river Roe in the North, and the town built on the locality gets its name from the circumstance (Limavaddy—Dog’s leap). We have more than one large pool deriving its name from having been infested by a worm or a serpent in the days of the heroes. Fion M‘Cumhaill killed several of these. A Munster champion slew a terrible specimen in the Duffrey (Co. Wexford), and the pool in which it sweltered is yet called Loch‐na‐Piastha. Near that remarkable piece of water is a ridge, called Kilach dermid (Cullach Diarmuid, Diarmuid’s Boar). Even p. 13 the domestic hen gives a name to a mountain in Londonderry, Sliabh Cearc,6 and to a castle in Connaught, Caislean na Cearca. The dog has a valley in Roscommon (Glann na Moddha) to himself, and the pig (muc), among his possessions, owns more than one line of vale. Fion’s exploits in killing terrible birds with his arrows, the boar that ravaged the great valley in Munster, and the various “piasts” in the lakes, bring him on a line with the Grecian Hercules. And as the old Pagans of that country and of Italy, along with a wholesome dread and hatred of the Stymphalides, hydras, and lions, warred on by Hercules, together with the Harpies and Cerberus, entertained for them a certain fetish reverence, so it is not to be wondered at if the secluded Celts of Ireland regarded their boars, and serpents, and cats, with similar feelings. Mr. Hackett relates a legend of a monster (genus and species not specified) who levied black mail in the form of flesh meat on a certain district in Cork to such an amount that they apprehended general starvation. In this exigency they applied to a holy man, and acting under his directions, they called the terrible tax‐collector to a parley. They represented to him that they were nearly destitute of means to furnish his honour with another meal, but that if he consented to enter a certain big pot, and sleep till p. 14 Monday, they would scatter themselves abroad, and collect such a supply of fish and flesh as would satisfy his appetite for a twelvemonth. Thinking the offer reasonable, he got into his crib, which was securely covered by his wily constituents, and dropped into an exceedingly deep hole in the neighbouring river. He looked on this as a strange proceeding, but kept his opinion to himself until next Monday. Then he roared out to be set at liberty, but the unprincipled party with whom he had to do, stated that the time appointed had not arrived, seeing that Doomsday was the period named in the covenant. He insisted that Monday was the word, but learned, to his great disgust, that the Celtic name, besides doing duty for that first of working days, also implied the Day of Judgment. He gave a roar, and stupidly vented his rage in a stanza of five lines, to the effect that if he was once more at liberty he would not only eat up the whole country, but half the world into the bargain; and bitterly bewailed his ignorance of the perfidies of the Gaelic tongue, that had made him a wretched prisoner.

These observations on animal worship cannot be better brought to a close than by the mention of the cat who reigned over the Celtic branch of the feline race at Knobba, in Meath. The talented and very ill‐tempered chief bard, Seanchan, satirized the mice in a body, and the cats also, including their king, for allowing p. 15 the contemptible vermin to thrust their whiskers into the egg intended for his dinner. He was at Cruachan in Connaught at the time, but the venom of his verse disagreeably affected King Irusan, in his royal cave at Knowth, on the Boyne. He (the cat) took the road, and never stopped for refreshment, till, in the presence of the full court at Cruachan, he seized on the pestilent poet, and throwing him on his back, swept eastwards across the Shannon in full career. His intent was to take him home and make a sumptuous meal of him, assisted by Madame Sharptooth, his spouse, their daughter of the same name, and Roughtooth and the Purrer, their sons. However, as he was cantering through Clonmacnois, St. Kiaran, who, like his Saxon brother, St. Dunstan, was a skilful worker in metals, espied him while hammering on a long red‐hot bar of iron. The saint set very small value on Seanchan as a bard, but, regarding him as a baptized man, he determined to disappoint the revengeful Irusan. Rushing out of his workshop, and assuming the correct attitude of a spear‐thrower, he launched the flaming bar, which, piercing the cat near the flank, an inch behind the helpless body of the bard, passed through and through, stretched the feline king expiring in agony, and gave the ill‐conditioned poet a space for repentance.

Not only can a general resemblance be traced in all p. 16 the fictions of the great Japhetian divisions of the human race, but an enthusiastic and diligent explorer would be able to find a relationship between these and the stories current among the Semitic races, and even the tribes scattered over the great continent of Africa, subject to the variations arising from climate, local features, and the social condition of the people. One instance must suffice. In the cold north the fox persuaded the bear to let down his tail into a pond to catch fish, just as the frost was setting in. When a time sufficient for Reynard’s purpose had elapsed, he cried out, “Pull up the line, you have got a bite.” The first effort was to no purpose. “Give a stouter pull—there is a great fish taken;” and now the bear put such a will in his strain that he left his tail under the ice. Since that time the family of Bruin are distinguished by stumpy tails. In Bournou, in Africa, where ice is rather scarce, the weasel said to the hyena, “I’ve just seen a large piece of flesh in such a pit. It is too heavy for me, but you can dip down your tail and I will fasten the meat to it, and then you have nothing to do but give a pull.” “All right,” said the hyena. When the tail was lowered, the weasel fastened it to a stout cross‐stick, and gave the word for heaving. No success at first; then he cried out, “The meat is heavy—pull as if you were in earnest.” At the second tug the tail was left behind, and ever since, hyenas have no tails worth mentioning.

p. 17The chief incidents of the following household tale would determine its invention to a period subsequent to the introduction of Christianity; but it would not have been difficult for a Christian story‐teller to graft the delay of the baptism on some Pagan tale. It is slightly connected with the “Lassie and her Godmother” in the Norse collection. An instance of the rubbing‐down process to which these old‐world romances are subject in their descent through the generations of story‐tellers, is the introduction of the post‐office and its unworthy officer, long before the round ruler and the strip of parchment formed the writing apparatus of the kings of Sparta or their masters, the Ephori.

Once there was a king, and he had two fine children, a girl and a boy; but he married again after their mother died, and a very wicked woman she was that he put over them. One day when he was out hunting, the stepmother came in where the daughter was sitting all alone, with a cup of poison in one hand and a dagger in the other, and made her swear that she would never tell any one that ever was christened what she would see her doing. The poor young girl—she was only fifteen—took the oath, and just after the queen took the king’s favourite dog and killed him before her eyes.

When the king came back, and saw his pet lying dead in the hall, he flew into a passion, and axed who done7 p. 18 it; and says the queen, says she—“Who done it but your favourite daughter? There she is—let her deny it if she can!” The poor child burst out a crying, but wasn’t able to say anything in her own defence bekase of her oath. Well, the king did not know what to do or to say. He cursed and swore a little, and hardly ate any supper. The next day he was out a hunting the queen killed the little son, and left him standing on his head on the window‐seat of the lobby.

Well, whatever way the king was in before, he went mad now in earnest. “Who done this?” says he to the queen. “Who, but your pet daughter?” “Take the vile creature,” says he to two of his footmen, “into the forest, and cut off her two hands at the wrists, and maybe that’ll teach her not to commit any more murders. Oh, Vuya, Vuya!” says he, stamping his foot on the boarded floor, “what a misfortunate king I am to lose my childher this way, and had only the two. Bring me back the two hands, or your own heads will be off before sunset.”

When he stamped on the floor a splinter ran up into his foot through the sole of his boot; but he didn’t mind it at first, he was in such grief and anger. But when he was taking off his boots, he found the splinter fastening one of them on his foot. He was very hardset to get it off, and was obliged to send for a surgeon to get the splinter out of the flesh; but the more he cut and probed, the further it went in. So he was obliged to lie on a sofia all day, and keep it poulticed with bowl‐almanac or some other plaster.

Well, the poor princess, when her arms were cut off, thought the life would leave her; but she knew there was a holy well off in the wood, and to it she made her way. She put her poor arms into the moss that was growing over it, and the blood stopped flowing, and she was eased of the pain, and then she washed herself as well as she could. She fell asleep by the well, and the spirit of her mother appeared to her in a dream, and told her to be good, and never forget to say her prayers p. 19 night and morning, and that she would escape every snare that would be laid for her.

When she awoke next morning she washed herself again, and said her prayers, and then she began to feel hungry. She heard a noise, and she was so afraid that she got into a low broad tree that hung over the well. She wasn’t there long till she saw a girl with a piece of bread and butter in one hand, and a pitcher in the other, coming and stooping over the well. She looked down through the branches, and if she did, so sure the girl saw her face in the water, and thought it was her own. She looked at it again and again, and then, without waiting to eat her bread or fill her pitcher, she ran back to the kitchen of a young king’s palace that was just at the edge of the wood. “Where’s the water?” says the housekeeper. “Wather!” says she; “it ’ud be a purty business for such handsome girl as I grew since yesterday, to be fetchin’ wather for the likes of the people that’s here. It’s married to the young prince I ought to be.” “Oh! to Halifax with you,” says the housekeeper, “I’ll soon cure your impedence.” So she locked her up in the store‐room, an’ kep’ her on bread and water.

To make a long story short, two other girls were sent to the well, and all were in the same story when they cum back. An’ there was such a thravally8 ruz in the kitchen about it at last, that the young king came to hear the rights of it. The last girl told him what happened to herself, and nothing would do the prince but go to the well to see about it. When he came he stooped and saw the shadow of the beautiful face; but he had sense enough to look up, and he found the princess in the tree.

Well, it would take me too long to tell yez all the fine things he said to her, and how modestly she answered him, and how he handed her down, and was almost p. 20 ready to cry when he seen her poor arms. She would not tell him who she was, nor the way she was persecuted on account of her oath; but the short and the long of it was, that he took her home, and couldn’t live if she didn’t marry him. Well, married they were; and in course of time they had a fine little boy; but the strangest thing of all was that the young queen begged her husband not to have the child baptized till he’d be after coming home from the wars that the King of Ireland had just then with the Danes.

He agreed, and set off to the camp, giving a beautiful jewel to her just as his foot was in the stirrup. Well, he wrote to her every second day, and she wrote to him every second day, and dickens a letter ever came to the hands of him or her. For the wicked stepmother had her watched all along, from the very day she came to the well till the king went to the wars; and she gave such a bribe to the postman (!) that she got all the letters herself. Well, the poor king didn’t know whether he was standing on his head or his feet, and the poor queen was crying all the day long.

At last there was a letter delivered to the king; and this was wrote by the wicked stepmother herself, as if it was from the young queen to one of the officers, asking him to get a furlough, and come and meet her at such a well, naming the one in the forest. He got this officer, that was as innocent as the child unborn, put in irons, and sent two of his soldiers to put the queen to death, and bring him his young child safe. But the night before, the spirit of the queen’s mother appeared to her in a dream, and told her the danger that was coming. “Go,” said she, “with your child to‐morrow morning to the well, and dress yourself in your maid’s clothes before you leave the house; wash your arms in the well once more, and take a bottle of the water with you, and return to your father’s palace. Nobody will know you. The water will cure him of a disorder he has, and I need not say any more.”

p. 21Just as the young queen was told, just so she done; and when she was after washing her face and arms, lo and behold! her nice soft hands were restored; but her face that was as white as cream was now as brown as a berry. So she fell on her knees and said her prayers, and then she filled her bottle, and set out for her father’s court with her child in her arms. The sentries at the palace gates let her pass when she said she was coming to cure the king; and she got to where he was lying in pain before the stepmother knew anything about it, for herself was sick at the time.

Before she opened her mouth the king loved her, she looked so like his former queen and his lost daughter, though her face was so swarthy. She hardly washed his wound with the water of the holy well when out came the splinter, and he was as strong on his limbs as a new ditch.

Well, hadn’t he great cooramuch about the brown‐faced woman and her child, and nothing that the wicked queen could do would alter his opinion of her. The old rogue didn’t know who she was, especially as she wasn’t without the hands; but it was her nature to be jealous of every one that the king cared for.

In two or three weeks the wars was over, and the young king was returning home, and the road he took brought him by his father‐in‐law’s. The old king would not let him pass by without giving him an entertainment for all his bravery again’ the Danes, and there was great huzzaing and cheering as he was riding up the avenue and through the courtyard. Just as he was alighting, his wife held up his little son to him, with the jewel in his little hand.

He got a wonderful fright. He knew his wife’s features, but they were so tawny, and her pretty brown hands were to the good, and the child was his own picture, but still she couldn’t be his false princess. He kissed the child, and passed on, but hardly said a word till dinner was over. Then says he to the old king, “Would you p. 22 allow a brown woman and her child that I saw in the palace yard, to be sent for, till I speak to her?” “Indeed an’ I will,” said the other; “I owe my life to her.” So she came in, and the young king made her sit down very close to him. “Young woman,” says he, “I have a particular reason for asking who you are, and who is the father of that child.” “I can’t tell you that, sir,” said she, “because of an oath I was obliged to take never to tell my story to any one that was christened. But my little boy was never christened, and to him I’ll tell everything. My little son, you must know that my wicked stepmother killed my father’s favourite dog, and killed my own little brother, and made me swear never to tell any one that ever received baptism, about it. She got my own father to have my hands chopped off, and I’d die only I washed them in the holy well in the forest. A king’s son made me his wife, and she got him by forged letters to send orders to have me killed. The spirit of my mother watched over me; my hands were restored; my father’s wound was healed; and now I place you in your own father’s arms. Now, you may be baptized, thank God! and that’s the story I had to tell you.”

She took a wet towel, and wiped her face, and she became as white and red as she was the day of her marriage. She had like to be hurt with her husband and her father pulling her from each other; and such laughing and crying never was heard before or since. If the wicked stepmother didn’t make her escape, she was torn between wild horses; and if they all didn’t live happy after—that you and I may!”

We heard the following household narrative only once. The narrator, Jemmy Reddy, was a young lad whose father’s garden was on the line between the rented land of Ballygibbon, and the Common of the White Mountain (the boundary between Wexford and Carlow counties), p. 23 consequently on the very verge of civilization. He was gardener, ploughman, and horseboy, to the Rev. Mr. M. of Coolbawn, at the time of the learning of this tale. We had once the misfortune to be at a wake, when the adventures of another fellow with a goat‐skin, not at all decent, were told by a boy with a bald head, rapidly approaching his eightieth year. Jemmy Reddy’s story has nothing in common with it but the name. We recognised the other in Mr. Campbell’s “Tales of the Highlands,” very much disguised; but, even in that tolerably decent garb, not worth preserving. The following avowal is made with some reluctance. Forty or fifty years since, several very vile tales—as vile as could be found in the “Fabliaux,” or the “Decameron,” or any other dirty collection, had a limited circulation among farm‐servants and labourers, even in the respectable county of Wexford. It was one of these that poor old T. L. told. Let us hope that it has vanished from the collections still extant in our counties of the Pale.

Long ago, a poor widow woman lived down near the iron forge, by Enniscorthy, and she was so poor, she had no clothes to put on her son; so she used to fix him in the ash‐hole, near the fire, and pile the warm ashes about him; and according as he grew up, she sunk the pit deeper. At last, by hook or by crook, she got a goat‐skin, p. 24 and fastened it round his waist, and he felt quite grand, and took a walk down the street. So says she to him next morning, “Tom, you thief, you never done any good yet, and you six foot high, and past nineteen;—take that rope, and bring me a bresna from the wood.” “Never say ’t twice, mother,” says Tom—“here goes.”

When he had it gathered and tied, what should come up but a big joiant, nine foot high, and made a lick of a club at him. Well become Tom, he jumped a‐one side, and picked up a ram‐pike; and the first crack he gave the big fellow, he made him kiss the clod. “If you have e’er a prayer,” says Tom, “now’s the time to say it, before I make brishe10 of you.” “I have no prayers,” says the giant; “but if you spare my life I’ll give you that club; and as long as you keep from sin, you’ll win every battle you ever fight with it.”

Tom made no bones about letting him off; and as soon as he got the club in his hands, he sat down on the bresna, and gave it a tap with the kippeen, and says, “Bresna, I had great trouble gathering you, and run the risk of my life for you; the least you can do is to carry me home.” And sure enough, the wind o’ the word was all it wanted. It went off through the wood, groaning and cracking, till it came to the widow’s door.

Well, when the sticks were all burned, Tom was sent off again to pick more; and this time he had to fight with a giant that had two heads on him. Tom had a little more trouble with him—that’s all; and the prayers he said, was to give Tom a fife, that nobody could help dancing when he was playing it. Begonies, he made the big fagot dance home, with himself sitting on it. Well, if you were to count all the steps from this to Dublin, dickens a bit you’d ever arrive there. The next giant was a beautiful boy with three heads on him. He had neither prayers nor catechism no more nor the others; and so he gave Tom a bottle of green ointment, that p. 25 wouldn’t let you be burned, nor scalded, nor wounded. “And now,” says he, “there’s no more of us. You may come and gather sticks here till little Lunacy Day in Harvest, without giant or fairy‐man to disturb you.”

Well, now, Tom was prouder nor ten paycocks, and used to take a walk down street in the heel of the evening; but some o’ the little boys had no more manners than if they were Dublin jackeens, and put out their tongues at Tom’s club and Tom’s goat‐skin. He didn’t like that at all, and it would be mean to give one of them a clout. At last, what should come through the town but a kind of a bellman, only it’s a big bugle he had, and a huntsman’s cap on his head, and a kind of a painted shirt. So this—he wasn’t a bellman, and I don’t know what to call him—bugle‐man, maybe, proclaimed that the King of Dublin’s daughter was so melancholy that she didn’t give a laugh for seven years, and that her father would grant her in marriage to whoever could make her laugh three times. “That’s the very thing for me to try,” says Tom; and so, without burning any more daylight, he kissed his mother, curled his club at the little boys, and off he set along the yalla highroad to the town of Dublin.

At last Tom came to one of the city gates, and the guards laughed and cursed at him instead of letting him in. Tom stood it all for a little time, but at last one of them—out of fun, as he said—drove his bagnet half an inch or so into his side. Tom done nothing but take the fellow by the scruff o’ the neck and the waistband of his corduroys, and fling him into the canal. Some run to pull the fellow out, and others to let manners into the vulgarian with their swords and daggers; but a tap from his club sent them headlong into the moat or down on the stones, and they were soon begging him to stay his hands.

So at last one of them was glad enough to show Tom the way to the palace‐yard; and there was the king, and the queen, and the princess, in a gallery, looking at all p. 26 sorts of wrestling, and sword‐playing, and rinka‐fadhas (long dances), and mumming,11 all to please the princess; but not a smile came over her handsome face.

Well, they all stopped when they seen the young giant, with his boy’s face, and long black hair, and his short, curly beard—for his poor mother couldn’t afford to buy razhurs—and his great strong arms, and bare legs, and no covering but the goatskin that reached from his waist to his knees. But an envious wizened basthard12 of a fellow, with a red head, that wished to be married to the princess, and didn’t like how she opened her eyes at Tom, came forward, and asked his business very snappishly. “My business,” says Tom, says he, “is to make the beautiful princess, God bless her, laugh three times.” “Do you see all them merry fellows and skilful swordsmen,” says the other, “that could eat you up with a grain of salt, and not a mother’s soul of ’em ever got a laugh from her these seven years?” So the fellows gathered round Tom, and the bad man aggravated him till he told them he didn’t care a pinch o’ snuff for the whole bilin’ of ’em; let ’em come on, six at a time, and try what they could do. The king, that was too far off to hear what they were saying, asked what did the stranger want. “He wants,” says the red‐headed fellow, “to make hares of your best men.” “Oh!” says the king, “if that’s the way, let one of ’em turn out and try his mettle.” So one stood forward, with soord and pot‐lid, and made a cut at Tom. He struck the fellow’s elbow with the club, and up over their heads flew the sword, and down went the owner of it on the gravel from a thump he got on the helmet. Another took his place, and another, and another, and then half‐a‐dozen at once, p. 27 and Tom sent swords, helmets, shields, and bodies, rolling over and over, and themselves bawling out that they were kilt, and disabled, and damaged, and rubbing their poor elbows and hips, and limping away. Tom contrived not to kill any one; and the princess was so amused, that she let a great sweet laugh out of her that was heard over all the yard. “King of Dublin,” says Tom, “I’ve quarter your daughter.” And the king didn’t know whether he was glad or sorry, and all the blood in the princess’s heart run into her cheeks.

So there was no more fighting that day, and Tom was invited to dine with the royal family. Next day, Redhead told Tom of a wolf, the size of a yearling heifer, that used to be serenading (sauntering) about the walls, and eating people and cattle; and said what a pleasure it would give the king to have it killed. “With all my heart,” says Tom; “send a jackeen to show me where he lives, and we’ll see how he behaves to a stranger.” The princess was not well pleased, for Tom looked a different person with fine clothes and a nice green birredh over his long curly hair; and besides, he’d got one laugh out of her. However, the king gave his consent; and in an hour and a half the horrible wolf was walking into the palace‐yard, and Tom a step or two behind, with his club on his shoulder, just as a shepherd would be walking after a pet lamb.

The king and queen and princess were safe up in their gallery, but the officers and people of the court that wor padrowling about the great bawn, when they saw the big baste coming in, gave themselves up, and began to make for doors and gates; and the wolf licked his chops, as if he was saying, “Wouldn’t I enjoy a breakfast off a couple of yez!” The king shouted out, “O Gilla na Chreck an Gour, take away that terrible wolf, and you must have all my daughter.” But Tom didn’t mind him a bit. He pulled out his flute and began to play like vengeance; and dickens a man or boy in the yard but began shovelling away heel and toe, and the wolf himself p. 28 was obliged to get on his hind legs and dance “Tatther Jack Walsh,” along with the rest. A good deal of the people got inside, and shut the doors, the way the hairy fellow wouldn’t pin them; but Tom kept playing, and the outsiders kept dancing and shouting, and the wolf kept dancing and roaring with the pain his legs were giving him: and all the time he had his eyes on Redhead, who was shut out along with the rest. Wherever Redhead went, the wolf followed, and kept one eye on him and the other on Tom, to see if he would give him leave to eat him. But Tom shook his head, and never stopped the tune, and Redhead never stopped dancing and bawling, and the wolf dancing and roaring, one leg up and the other down, and he ready to drop out of his standing from fair tiresomeness.

When the princess seen that there was no fear of any one being kilt, she was so divarted by the stew that Redhead was in, that she gave another great laugh; and, well become Tom, out he cried, “King of Dublin, I have two halves of your daughter.” “Oh, halves or alls,” says the king, “put away that divel of a wolf, and we’ll see about it.” So Gilla put his flute in his pocket, and says he to the baste that was sittin’ on his currabingo ready to faint, “Walk off to your mountain, my fine fellow, and live like a respectable baste; and if I ever find you come within seven miles of any town, I’ll——.” He said no more, but spit in his fist, and gave a flourish of his club. It was all the poor divel wanted: he put his tail between his legs, and took to his pumps without looking at man or mortial, and neither sun, moon, or stars ever saw him in sight of Dublin again.

At dinner every one laughed but the foxy fellow; and sure enough he was laying out how he’d settle poor Tom next day. “Well, to be sure!” says he, “King of Dublin, you are in luck. There’s the Danes moidhering us to no end. D—— run to Lusk wid ’em! and if any one can save us from ’em, it is this gentleman with the goatskin. There is a flail hangin’ on the collar‐beam in p. 29 hell, and neither Dane nor devil can stand before it.” “So,” says Tom to the king, “will you let me have the other half of the princess if I bring you the flail?” “No, no,” says the princess; “I’d rather never be your wife than see you in that danger.”

But Redhead whispered and nudged Tom about how shabby it would look to reneague the adventure. So he asked which way he was to go, and Redhead directed him through a street where a great many bad women lived, and a great many sheebeen houses were open, and away he set.

Well, he travelled and travelled, till he came in sight of the walls of hell; and, bedad, before he knocked at the gates, he rubbed himself over with the greenish ointment. When he knocked, a hundred little imps popped their heads out through the bars, and axed him what he wanted. “I want to speak to the big divel of all,” says Tom: “open the gate.”

It wasn’t long till the gate was thrune open, and the Ould Boy received Tom with bows and scrapes, and axed his business. “My business isn’t much,” says Tom. “I only came for the loan of that flail that I see hanging on the collar‐beam, for the King of Dublin to give a thrashing to the Danes.” “Well,” says the other, “the Danes is much better customers to me; but since you walked so far I won’t refuse. Hand that flail,” says he to a young imp; and he winked the far‐off eye at the same time. So, while some were barring the gates, the young devil climbed up, and took down the flail that had the handstaff and booltheen both made out of red‐hot iron. The little vagabond was grinning to think how it would burn the hands off o’ Tom, but the dickens a burn it made on him, no more nor if it was a good oak sapling. “Thankee,” says Tom. “Now would you open the gate for a body, and I’ll give you no more trouble.” “Oh, tramp!” says Ould Nick; “is that the way? It is easier getting inside them gates than getting out again. Take that tool from him, and give him a dose of the oil of p. 30 stirrup.” So one fellow put out his claws to seize on the flail, but Tom gave him such a welt of it on the side of the head that he broke off one of his horns, and made him roar like a devil as he was. Well, they rushed at Tom, but he gave them, little and big, such a thrashing as they didn’t forget for a while. At last says the ould thief of all, rubbing his elbow, “Let the fool out; and woe to whoever lets him in again, great or small.”

So out marched Tom, and away with him, without minding the shouting and cursing they kept up at him from the tops of the walls; and when he got home to the big bawn of the palace, there never was such running and racing as to see himself and the flail. When he had his story told, he laid down the flail on the stone steps, and bid no one for their lives to touch it. If the king, and queen, and princess, made much of him before, they made ten times more of him now; but Redhead, the mean scruffhound, stole over, and thought to catch hold of the flail to make an end of him. His fingers hardly touched it, when he let a roar out of him as if heaven and earth were coming together, and kept flinging his arms about and dancing, that it was pitiful to look at him. Tom run at him as soon as he could rise, caught his hands in his own two, and rubbed them this way and that, and the burning pain left them before you could reckon one. Well, the poor fellow, between the pain that was only just gone, and the comfort he was in, had the comicalest face that ever you see, it was such a mixtherum‐gatherum of laughing and crying. Everybody burst out a laughing—the princess could not stop no more than the rest; and then says Gilla, or Tom, “Now, ma’am, if there were fifty halves of you, I hope you’ll give me them all.” Well, the princess had no mock modesty about her. She looked at her father, and by my word, she came over to Gilla, and put her two delicate hands into his two rough ones, and I wish it was myself was in his shoes that day!

Tom would not bring the flail into the palace. You may be sure no other body went near it; and when the p. 31 early risers were passing next morning, they found two long clefts in the stone, where it was after burning itself an opening downwards, nobody could tell how far. But a messenger came in at noon, and said that the Danes were so frightened when they heard of the flail coming into Dublin, that they got into their ships, and sailed away.

Well, I suppose, before they were married, Gilla got some man, like Pat Mara of Tomenine, to larn him the “principles of politeness,” fluxions, gunnery and fortification, decimal fractions, practice, and the rule of three direct, the way he’d be able to keep up a conversation with the royal family. Whether he ever lost his time larning them sciences, I’m not sure, but it’s as sure as fate that his mother never more saw any want till the end of her days.

Let not the present compiler be censured for putting this catalogue of learned branches into the mouth of an uneducated boy. We have seen Reddy, and half the congregation of Rathnure Chapel, swallowing with eyes, mouths, and ears, the enunciation of the master’s assumed stock of knowledge, ornamented with flourishes, gamboge, verdigris, and vermilion, and set forth in the very order observed in the text.

In the Volksmärchen (People’s Stories), Hans (the diminutive of Johannes) performs the greater part of the exploits. His namesake Jack is the hero of the household stories of the more English counties of Ireland. The following is a fair specimen of the class:—

There was once a poor couple, and they had three sons, and the youngest’s name was Jack. One harvest day, the eldest fellow threw down his hook, and says he, “What’s the use to be slaving this way! I’ll go seek my fortune.” And the second son said the very same: and says Jack, “I’ll go seek my fortune along with you, but let us first leave the harvest stacked for the old couple.” Well, he over‐persuaded them, and bedad, as soon as it was safe, they kissed their father and mother, and off they set, every one with three pounds in his pocket, promising to be home again in a year and a day. The first night they had no better lodging than a fine dry dyke of a ditch, outside of a churchyard. Before they went to sleep, the youngest got inside to read the tombstones. What should he stumble over but a coffin, and the sod was just taken off where the grave was to be. “Some poor body,” says he, “that was without friends to put him in consecrated ground: he mustn’t be left this way.” So he threw off his coat, and had a couple of feet cleared out, when a terrible giant walked up. “What are you at?” says he; “the corpse owed me a guinea, and he sha’n’t be buried till it is paid.” “Well, here is your guinea,” says Jack, “and leave the churchyard: it’s nothing the better for your company.” Well, he got down a couple of feet more, when another uglier giant again, with two heads on him, came and stopped Jack with the same story, and got his guinea; and when the grave was six feet down, the third giant looks on him, and he had three heads. So Jack was obliged to part with his three guineas before he could put the sod over the poor man. Then he went and lay down by his brothers, and slept till the sun began to shine on their faces next morning.

They soon came to a cross‐road, and there every one took his own way. Jack told them how all his money p. 33 was gone, but not a farthing did they offer him. Well, after some time, Jack found himself hungry, and so he sat down by the road side, and pulled out a piece of cake and a lump of bacon. Just as he had the first bit in his mouth, up comes a poor man, and asks something of him for God’s sake. “I have neither brass, gold, nor silver about me,” says Jack; “and here’s all the provisions I’m master of. Sit down and have a share.” Well, the poor man didn’t require much pressing, and when the meal was over, says he, “Sir, where are you bound for?” “Faith, I don’t know,” says Jack; “I’m going to seek my fortune.” “I’ll go with you for your servant,” says the other. “Servant inagh (forsooth)! bad I want a servant—I, that’s looking out for a place myself.” “No matter. You gave Christian burial to my poor brother yesterday evening. He appeared to me in a dream, and told me where I’d find you, and that I was to be your servant for a year. So you’ll be Jack the master, and I Jack the servant.” “Well, let it be so.”

After sunset, they came to a castle in a wood, and “Here,” says the servant, “lives the giant with one head, that wouldn’t let my poor brother be buried.” He took hold of a club that hung by the door, and gave two or three thravallys on it. “What do yous want?” says the giant, looking out through a grating. “Oh, sir, honey!” says Jack, “we want to save you. The king is sending 100,000 men to take your life for all the wickedness you ever done to poor travellers, and that. So because you let my brother be buried, I came to help you.” “Oh, murdher, murdher, what’ll I do at all at all?” says he. “Have you e’er a hiding‐place?” says Jack, “I have a cave seven miles long, and it opens into the bawn.” “That’ll do. Leave a good supper for the men, and then don’t stir out of your pew till I call you.” So they went in, and the giant left a good supper for the army, and went down, and they shut the trap‐door down on him.

Well, they ate and they drank, and then Jack gother all the horses and cows, and drove them over an hether p. 34 the trap‐door, and such fighting and shouting, whinnying and lowing, as they had, and such noise as they made! Then Jack opened the door, and called out, “Are you there, sir?” “I am,” says he, from a mile or two inside. “Wor you frightened, sir?” “You may say frightened. Are they gone away?” “Dickens a go they’ll go till you give them your sword of sharpness.” “Cock them up with the sword of sharpness. I won’t give them a smite of it.” “Well, I think you’re right. Look out. They’ll be down with you in the twinkling of a harrow pin. Go to the end of the cave, and they won’t have your head for an hour to come.” “Well, that’s no great odds; you’ll find it in the closet inside the parlour. D—— do ’em good with it.” “Very well,” says Jack; “when they’re all cleared off, I’ll drop a big stone on the trap‐door.” So the two Jacks slept very combustible in the giant’s bed—it was big enough for them; and next morning, after breakfast, they dropped the big stone on the trap‐door, and away they went.

That night they slept at the castle of the two‐headed giant, and got his cloak of darkness in the same way; and the next night they slept at the castle of the three‐headed giant, and got his shoes of swiftness; and the next night they were near the king’s palace. “Now,” says Jack the servant, “this king has a daughter, and she was so proud that twelve princes killed themselves for her, because she would not marry any of them. At last the King of Moróco thought to persuade her, and the dickens a bit of him she’d have no more nor the others. So he fell on his sword, and died; and the old boy got leave to give him a kind of life again, to punish the proud lady. Maybe it’s an imp from hell is in his appearance. He lives in a palace one side of the river, and the king’s palace is on the other, and he has got power over the princess and her father; and when they have the heads of twelve courtiers over the gate, the King of Moróco will have the princess to himself, and maybe the evil spirit will have them both. Every young man p. 35 that offers himself has to do three things, and if he fails in all, up goes his head. There you see them—eleven, all black and white, with the sun and rain. You must try your hand. God is stronger than the devil.”

So they came to the gate. “What do you want?” says the guard. “I want to get the princess for my wife.” “Do you see them heads?” “Yes; what of that?” “Yours will be along with them before you’re a week older.” “That’s my own look out.” “Well, go on. God help all foolish people!” The king was on his throne in the big hall, and the princess sitting on a golden chair by his side. “Death or my daughter, I suppose,” says the king to Jack the master. “Just so, my liege,” says Jack. “Very well,” says the king. “I don’t know whether I’m glad or sorry,” says he. “If you don’t succeed in the three things, my daughter must marry the King of Moróco. If you do succeed, I suppose we’ll be eased from the dog’s life we are leading. I’ll leave my daughter’s scissors in your bedroom to‐night, and you’ll find no one going in till morning. If you have the scissors still at sunrise, your head will be safe for that day. Next day you must run a race against the King of Moróco, and if you win, your head will be safe that day too. Next day you must bring me the King of Moróco’s head, or your own head, and then all this bother will be over one way or the other.”

Well, they gave the two a good supper, and one time the princess would look sweet at Jack, and another time sour; for you know she was under enchantment. Sometimes she’d wish him killed, sometimes she’d like him to be saved.

When they went into their bedroom, the king came in along with them, and laid the scissors on the table. “Mind that,” says he, “and I’m sure I don’t know whether I wish to find it there to‐morrow or not.” Well, poor Jack was a little frightened, but his man encouraged him. “Go to bed,” says he; “I’ll put on the cloak of darkness, and watch, and I hope you’ll find the scissors p. 36 there at sunrise.” Well, bedad he couldn’t go to sleep. He kept his eye on the scissors till the dead hour, and the moment it struck twelve no scissors could he see: it vanished as clean as a whistle. He looked here, there, and everywhere—no scissors. “Well,” says he, “there’s hope still. Are you there, Jack?” but no answer came. “I can do no more,” says he. “I’ll go to bed.” And to bed he went, and slept.

Just as the clock was striking, Jack in the cloak saw the wall opening, and the princess walking in, going over to the table, taking up the scissors, and walking out again. He followed her into the garden, and there he saw herself and her twelve maids going down to the boat that was lying by the bank. “I’m in,” says the princess; “I’m in,” says one maid; and “I’m in,” says another; and so on till all were in; and “I’m in,” says Jack. “Who’s that?” says the last maid. “Go look,” says Jack. Well, they were all a bit frightened. When they got over, they walked up to the King of Moróco’s palace, and there the King of Moróco was to receive them, and give them the best of eating and drinking, and make his musicianers play the finest music for them.

When they were coming away, says the princess, “Here’s the scissors; mind it or not as you like.” “Oh, won’t I mind it!” says he. “Here you go,” says he again, opening a chest, and dropping it into it, and locking it up with three locks. But before he shut down the lid, my brave Jack picked up the scissors, and put it safe into his pocket. Well, when they came to the boat, the same things were said, and the maids were frightened again.

When Jack the master awoke in the morning, the first thing he saw was the scissors on the table, and the next thing he saw was his man lying asleep in the other bed, the next was the cloak of darkness hanging on the bed’s foot. Well, he got up, and he danced, and he sung, and he hugged Jack; and when the king came in with a troubled face, there was the scissors safe and sound. p. 37 “Well, Jack,” says he, “you’re safe for one day more.” The king and princess were more meentrach (loving) to Jack to‐day than they were yesterday, and the next day the race was to be run.

At last the hour of noon came, and there was the King of Moróco with tight clothes on him—themselves, and his hair, and his eyes as black as a crow, and his face as yellow as a kite’s claw. Jack was there too, and on his feet were the shoes of swiftness. When the bugle blew, they were off, and Jack went seven times round the course while the king went one: it was like the fish in the water, the arrow from a bow, the stone from a sling, or a star shooting in the night. When the race was won, and the people were shouting, the black king looked at Jack like the very devil himself, and says he, “Don’t holloa till you’re out of the wood—to‐morrow your head or mine.” “Heaven is stronger than hell,” says Jack.

And now the princess began to wish in earnest that Jack would win, for two parts of the charm were broke. So some one from her told Jack the servant that she and her maids should pay their visit to the Black Fellow at midnight like every other night past. Jack the servant was in the garden in his cloak when the hour came, and they all said the same words, and rowed over, and went up to the palace like as they done before.

The king was in a great state of fear and anger, and scolded the princess, and she didn’t seem to care much about it; but when they were leaving she said, “You know to‐morrow is to have your head or Jack’s head off. I suppose you will stay up all night!” He was standing on the grass when they were getting into the boat, and just as the last maid had her foot on the edge of it, Jack swept off his head with the sword of sharpness just as if it was the head of a thistle, and put it under his cloak. The body fell on the grass and made no noise. Well, the same moment the princess felt any liking she had for him all gone like last year’s snow, and she began to sob p. 38 and cry for fear of any thing happening to Jack. The maids were not very good at all, and so, from the moment they got out of the boat, Jack kept knocking the head against their faces and their legs, and made them roar and bawl till they were inside of the palace.

The first thing Jack the master saw when he woke in the morning, was the black head on the table, and didn’t he jump up in a hurry! When the sun was rising, every one in the palace, great and small, were in the bawn before Jack’s window, and the king was at the door. “Jack,” said he, “if you havn’t the King of Moróco’s head on a gad, your own will be on a spear, my poor fellow.” But just at the moment he heard a great shout from the bawn. Jack the servant was after opening the window, and holding out the King of Moróco’s head by the long black hair.

So the princess, and the king, and all were in joy, and maybe they didn’t keep the wedding long a‐waiting. A year and a day after Jack left home, himself and his wife were in their coach at the cross‐roads, and there were the two poor brothers, sleeping in the ditch with their reaping‐hooks by their sides. They wouldn’t believe Jack at first that he was their brother, and then they were ready to eat their nails for not sharing with him that day twelvemonth. They found their father and mother alive, and you may be sure they left them comfortable. So you see what a good thing in the end it is to be charitable to the poor, dead or alive.

In some versions of “Jack the Master,” &c. Jack the servant is the spirit of the buried man. He aids and abets his master in leaving the giants interred alive in their caves, and carrying off their gold and silver, and he helps him to cheat his future father‐in‐law at cards, and bears a hand in other proceedings, most disgraceful to p. 39 any ghost encumbered with a conscience. As originally told, the anxiety of the hero to bestow sepulchral rites on the corpse, arose from his wish to rescue the soul from its dismal wanderings by the gloomy Styx. In borrowing these fictions from their heathen predecessors, the Christian storytellers did not take much trouble to correct their laxity on the subject of moral obligations. Theft, manslaughter, and disregard of marriage vows, often pass uncensured by the free and easy narrator.

Silly as the poor hero of next tale may appear, he is kept in countenance by the German “Hans in Luck,” by the world‐renowned Wise Men of Gotham, and even the sage Gooroo, of Hindoostan. In a version of the legend given by a servant girl, who came from the Roer in Kilkenny, and had only slight knowledge of English, Thigue distinguished himself by an exploit more worthy of his character than any in the text. He stood in the market, with a web of cloth under his arm for sale. “Bow wow,” says a dog, looking up at him. “Five pounds,” says Thigue; “Bow wow,” says the dog again. “Well, here it is for you,” says Thigue. His reception by his mother at eventide may be guessed.

Jack was twenty years old before he done any good for his family. So at last his mother said it was high time for him to begin to be of some use. So the next market p. 40 day she sent him to Bunclody (Newtownbarry), to buy a billhook to cut the furze. When he was coming back he kep’ cutting gaaches with it round his head, till at last it flew out of his hand, and killed a lamb that a neighbour was bringing home. Well, if he did, so sure was his mother obliged to pay for it, and Jack was in disgrace. “Musha, you fool,” says she, “couldn’t you lay the bill‐hook in a car, or stick it into a bundle of hay or straw that any of the neighbours would be bringing home?” “Well, mother,” said he, “it can’t be helped now; I’ll be wiser next time.”

“Now, Jack,” says she, the next Saturday, “you behaved like a fool the last time; have some wit about you now, and don’t get us into a hobble. Here is a fi’penny bit, and buy me a good pair (set) of knitting needles, and fetch ’em home safe.” “Never fear, mother.” When Jack was outside the town, coming back, he overtook a neighbour sitting on the side‐lace of his car, and there was a big bundle of hay in the bottom of it. “Just the safe thing,” says Jack, sticking the needles into it. When he came home he looked quite proud out of his good management. “Well, Jack,” says his mother, “where’s the needles?” “Oh, faith! they’re safe enough. Send any one down to Jem Doyle’s, and he’ll find them in the bundle of hay that’s in the car.” “Musha, purshuin to you, Jack! why couldn’t you stick them in the band o’ your hat? What searching there will be for them in the hay!” “Sure you said I ought to put any things I was bringing home in a car, or stick ’em in hay or straw. Anyhow I’ll be wiser next time.”

Next week Jack was sent to a neighbour’s house about a mile away, for some of her nice fresh butter. The day was hot, and Jack remembering his mother’s words, stuck the cabbage leaf that held the butter between his hat and the band. He was luckier this turn than the other turns, for he brought his errand safe in his hair and down along his clothes. There’s no pleasing some p. 41 people, however, and his mother was so vexed that she was ready to beat him.

There was so little respect for Jack’s gumption in the whole village after this, that he wasn’t let go to market for a fortnight. Then his mother trusted him with a pair of young fowl. “Now don’t be too eager to snap at the first offer you’ll get; wait for the second any way, and above all things keep your wits about you.” Jack got to the market safe. “How do you sell them fowl, honest boy?” “My mother bid me ax three shillings for ’em, but sure herself said I wouldn’t get it.” “She never said a truer word. Will you have eighteen pence?” “In throth an’ I won’t; she ordhered me to wait for a second‐offer.” “And very wisely she acted; here is a shilling.” “Well now, I think it would be wiser to take the eighteen pence, but it is better for me at any rate to go by her bidding, and then she can’t blame me.”

Jack was in disgrace for three weeks after making that bargain; and some of the neighbours went so far as to say that Jack’s mother didn’t show much more wit than Jack himself.

She had to send him, however, next market day to sell a young sheep, and says she to him, “Jack, I’ll have your life if you don’t get the highest penny in the market for that baste.” “Oh, won’t I!” says Jack. Well, when he was standing in the market, up comes a jobber, and asks him what he’d take for the sheep. “My mother won’t be satisfied,” says Jack, “if I don’t bring her home the highest penny in the market.” “Will a guinea note do you?” says the other. “Is it the highest penny in the market?” says Jack. “No, but here’s the highest penny in the market,” says a sleeveen that was listenin’, getting up on a high ladder that was restin’ again’ the market house: “here’s the highest penny, and the sheep is mine.”

Well, if the poor mother wasn’t heart‐scalded this time it’s no matter. She said she’d never lose more than a shilling a turn by him again while she lived; but she p. 42 had to send him for some groceries next Saturday for all that, for it was Christmas eve. “Now, Jack,” says she, “I want some cinnamon, mace, and cloves, and half a pound of raisins; will you be able to think of ’em?” “Able, indeed! I’ll be repatin’ ’em every inch o’ the way, and that won’t let me forget them.” So he never stopped as he ran along, saying “cinnamon, mace, and cloves, and half a pound of raisins;” and this time he’d have come home in glory, only he struck his foot again’ a stone, and fell down, and hurt himself.

At last he got up, and as he went limping on he strove to remember his errand, but it was changed in his mind to “pitch, and tar, and turpentine, and half a yard of sacking”—“pitch, and tar, and turpentine, and half a yard of sacking.” These did not help the Christmas dinner much, and his mother was so tired of minding him that she sent him along with a clever black man (match‐maker), up to the county Carlow, to get a wife to take care of him.

Well, the black man never let him open his mouth all the time the coortin’ was goin’ on; and at last the whole party—his friends, and her friends, were gathered into the priest’s parlour. The black man staid close to him for ’fraid he’d do a bull; and when Jack was married half a‐year, if he thought his life was bad enough before, he thought it ten times worse now; and told his mother if she’d send his wife back to her father, he’d never make a mistake again going to fair or market. But the wife cock‐crowed over the mother as well as over Jack; and if they didn’t live happy, that we may!

The ensuing household story has rather more of a Norse than Celtic air about it, though there are apparently no traces of it in Grimm’s or Dasent’s collections, except in the circumstances of the flight. Parts of the p. 43 story may be recognised in the West Highland Tales, but we have met with the tale in full nowhere in print. Jemmy Reddy, Father Murphy’s servant, the relater of the “Adventures of Gilla na Chreck an Gour,” told it to the occupants of the big kitchen hearth in Coolbawn, one long winter evening, nearly in the style in which it is here given, and no liberty at all has been taken with the incidents. The underground adventures seem to point to the Celtic belief in the existence of the “Land of Youth,” under our lakes. If it were ever told in Scandinavia, the spacious caverns of the Northern land would be substituted for our Tir‐na‐n‐Oge, with the bottom of the sea for its sky, and its own sun, moon, and stars. The editor of this series never heard a second recitation of this household story.

There was once a king, some place or other, and he had three daughters. The two eldest were very proud and uncharitable, but the youngest was as good as they were bad. Well, three princes came to court them, and two of them were the moral of the eldest ladies, and one was just as lovable as the youngest. They were all walking down to a lake, one day, that lay at the bottom of the lawn, just like the one at Castleboro’, and they met a poor beggar. The king wouldn’t give him anything, and the eldest princes wouldn’t give him anything, nor their sweethearts; but the youngest daughter and her true love did give him something, and kind words along with it, and that was better nor all.

p. 44When they got to the edge of the lake, what did they find but the beautifulest boat you ever saw in your life; and says the eldest, “I’ll take a sail in this fine boat;” and says the second eldest, “I’ll take a sail in this fine boat;” and says the youngest, “I won’t take a sail in that fine boat, for I am afraid it’s an enchanted one.” But the others overpersuaded her to go in, and her father was just going in after her, when up sprung on the deck a little man only seven inches high, and he ordered him to stand back. Well, all the men put their hands to their soords; and if the same soords were only thraneens they weren’t able to draw them, for all sthrenth was left their arms. Seven Inches loosened the silver chain that fastened the boat, and pushed away; and after grinning at the four men, says he to them, “Bid your daughters and your brides farewell for awhile. That wouldn’t have happened you three, only for your want of charity. You,” says he to the youngest, “needn’t fear, you’ll recover your princess all in good time, and you and she will be as happy as the day is long. Bad people, if they were rolling stark naked in gold, would not be rich. Banacht lath.” Away they sailed, and the ladies stretched out their hands, but weren’t able to say a word.

Well, they wern’t crossing the lake while a cat ’ud be lickin’ her ear, and the poor men couldn’t stir hand or foot to follow them. They saw Seven Inches handing the three princesses out o’ the boat, and letting them down by a nice basket and winglas into a draw‐well that was convenient, but king nor princes ever saw an opening before in the same place. When the last lady was out of sight, the men found the strength in their arms and legs again. Round the lake they ran, and never drew rein till they came to the well and windlass; and there was the silk rope rolled on the axle, and the nice white basket hanging to it. “Let me down,” says the youngest prince; “I’ll die or recover them again.” “No,” says the second daughter’s sweetheart, “I’m entitled to my turn before you.” And says the other, “I must get first p. 45 turn, in right of my bride.” So they gave way to him, and in he got into the basket, and down they let him. First they lost sight of him, and then, after winding off a hundred perches of the silk rope, it slackened, and they stopped turning. They waited two hours, and then they went to dinner, because there was no chuck made at the rope.

Guards were set till next morning, and then down went the second prince, and sure enough, the youngest of all got himself let down on the third day. He went down perches and perches, while it was as dark about him as if he was in a big pot with the cover on. At last he saw a glimmer far down, and in a short time he felt the ground. Out he came from the big lime‐kiln, and lo and behold you, there was a wood, and green fields, and a castle in a lawn, and a bright sky over all. “It’s in Tir‐na‐n‐Oge I am,” says he. “Let’s see what sort of people are in the castle.” On he walked, across fields and lawn, and no one was there to keep him out or let him into the castle; but the big hall‐door was wide open. He went from one fine room to another that was finer, and at last he reached the handsomest of all, with a table in the middle; and such a dinner as was laid upon it! The prince was hungry enough, but he was too mannerly to go eat without being invited. So he sat by the fire, and he did not wait long till he heard steps, and in came Seven Inches and the youngest sister by the hand. Well, prince and princess flew into one another’s arms, and says the little man, says he, “Why aren’t you eating?” “I think, sir,” says he, “it was only good manners to wait to be asked.” “The other princes didn’t think so,” says he. “Each o’ them fell to without leave or licence, and only gave me the rough side o’ their tongue when I told them they were making more free than welcome. Well, I don’t think they feel much hunger now. There they are, good marvel instead of flesh and blood,” says he, pointing to two statues, one in one corner, and the other in the other corner of the room. The prince was p. 46 frightened, but he was afraid to say anything, and Seven Inches made him sit down to dinner between himself and his bride; and he’d be as happy as the day is long, only for the sight of the stone men in the corner. Well, that day went by, and when the next came, says Seven Inches to him: “Now, you’ll have to set out that way,” pointing to the sun; “and you’ll find the second princess in a giant’s castle this evening, when you’ll be tired and hungry, and the eldest princess to‐morrow evening; and you may as well bring them here with you. You need not ask leave of their masters; they’re only housekeepers with the big fellows. I suppose, if they ever get home, they’ll look on poor people as if they were flesh and blood like themselves.”

Away went the prince, and bedad, it’s tired and hungry he was when he reached the first castle, at sunset. Oh, wasn’t the second princess glad to see him! and if she didn’t give him a good supper, it’s a wonder. But she heard the giant at the gate, and she hid the prince in a closet. Well, when he came in, he snuffed, an’ he snuffed, an’ says he, “Be (by) the life, I smell fresh mate.” “Oh,” says the princess, “it’s only the calf I got killed to‐day.” “Ay, ay,” says he, “is supper ready?” “It is,” says she; and before he ruz from the table he hid three‐quarters of the calf, and a cag of wine. “I think,” says he, when all was done, “I smell fresh mate still.” “It’s sleepy you are,” says she; “go to bed.” “When will you marry me?” says the giant. “You’re puttin’ me off too long.” “St. Tibb’s Eve,” says she. “I wish I knew how far off that is,” says he; and he fell asleep, with his head in the dish.

Next day, he went out after breakfast, and she sent the prince to the castle where the eldest sister was. The same thing happened there; but when the giant was snoring, the princess wakened up the prince, and they saddled two steeds in the stables, and magh go bragh (the field for ever) with them. But the horses’ heels struck the stones outside the gate, and up got the giant, p. 47 and after them he made. He roared and he shouted, and the more he shouted, the faster ran the horses; and just as the day was breaking, he was only twenty perches behind. But the prince didn’t leave the castle of Seven Inches without being provided with something good. He reined in his steed, and flung a short, sharp knife over his shoulder, and up sprung a thick wood between the giant and themselves. They caught the wind that blew before them, and the wind that blew behind them did not catch them. At last they were near the castle where the other sister lived; and there she was, waiting for them under a high hedge, and a fine steed under her.